Animal Sex in the City

Lovebirds, human and otherwise, have long flocked to the California Academy of Sciences to connect with nature—and each other. Countless couples have hosted water-lit weddings at Steinhart Aquarium, and our NightLife series is often a hotspot for first-time Tinder couples. The Academy has even earned the dubious distinction of being the best place to make out in San Francisco.

Indeed, amorous activities are not just limited to humans. Many species at the Academy have a sex life, producing larvae, eggs, and baby animals that awe our visitors, and may even be key to protecting and saving species in the wild. Whether it be hatching penguin chicks or spawning thousands of tiny coral gametes, our scientists work tirelessly to discover new ways to regenerate the natural world and encourage animal resilience in the face of threats like climate change and habitat loss.

This Valentine’s Day, celebrate the unique ways Academy creatures do the deed, from our famously faithful penguins to our beautiful but brainless bat stars.

As a virologist, I’m fascinated by how the tiniest organisms, microbes, and viruses reproduce, sexually and otherwise!—that includes the microscopic face mites that lurk in our eyebrows and hair follicles. We share a long-standing relationship with these mites, who live virtually unnoticed in the hair follicles on our skin and feed on our oily sebum.

At night, these tiny microbes awake from their slumber, become active, and often hop between humans that sleep together, the microbes enjoying both the intimacy and proximity of pillow talk. After a mite mating session, females will lay eggs in our hair follicles and sebaceous glands, with the next generation of mini-mites hatching a few days later.

The Academy has introduced many couples to each other’s face mites, swabbing guest’s eyebrows and hair follicles at past NightLife events. Though research suggests that people in different parts of the world have different face mites, some couples learn they have a lot of microbial matter in common.

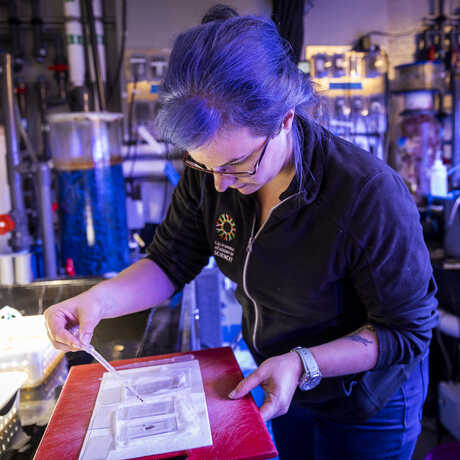

Rebecca Albright, an Academy curator of Invertebrate Zoology, is almost literally a doctor of coral love. As ocean warming and climate change cause coral reef bleaching across the world, Albright and Academy scientists are testing their resilience and encouraging their growth at the Coral Regeneration Lab (CoRL).

Under Albright’s supervision, the Academy became the first aquarium in the United States to spawn coral in a lab setting—and they’ve recently bred a second generation of coral from those original spawns.

Creating a coral family tree is no easy process, requiring some intensely monitored mood-setting. Because corals use environmental cues to reproduce, Albright and scientist Elora Lopez-Nandam will adjust an enclosure’s water temperature and change lighting to simulate natural seasonal and lunar cycles, all factors that trigger coral spawning.

Once the team sets the mood, the spawning event unfolds: Corals release tens of thousands of tiny, couscous-sized gamete “bundles”—packets of sperm surrounded by unfertilized eggs—into surrounding water. These bundles burst, mingle and fertilize, and then transform into free-swimming larvae in search of a place to call home.

"Three years ago, our team successfully bred baby corals in our public aquaria,” Albright said. “Recently, those same corals started spawning, meaning this is the first year that we closed the loop on the coral life cycle. It almost feels like I'm a coral grandma!”

Kathryn Whitney © California Academy of Sciences

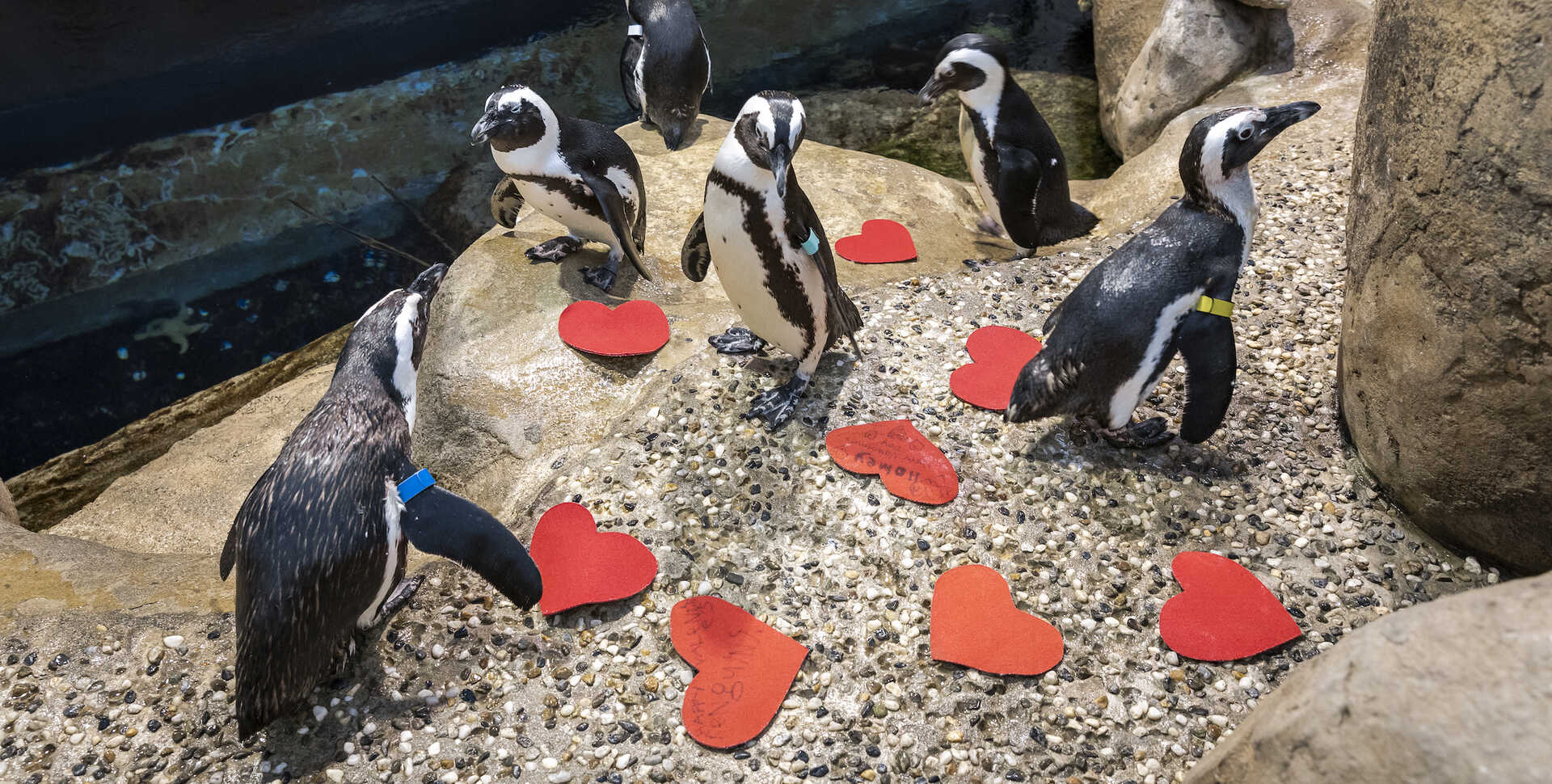

It’s no secret that African penguins (Spheniscus demersus) mate for life. At the Academy, our lover birds are also mating for the survival of their species.

Since 2022, Academy penguins have hatched 10 chicks, bred as part of a collaborative breeding and transfer program among Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA)-accredited institutions. The Species Survival Plan (SSP) supports aquariums including Steinhart in their shared work to help protect the critically endangered African penguins by maintaining genetic diversity of the population in human care.

It also lets our biologists play matchmaker.

“We describe [the SSP process to match mates] as a cross between Ancestry.com and Tinder: We think about the penguin’s genetics and family history to make recommendations for bonding pairs that will create healthy chicks,” said Senior Biologist Holly Rosenblum. “Once a pair of penguins sees each other alone in a room, well, the magic usually happens! It’s love at first sight.”

A fortuitous pairing of Bernie and Stanlee, matched for their complementary genetics, resulted in a batch of new hatchlings over Thanksgiving weekend in 2023—two of the five total chicks this pair has hatched. Even childless penguin pairs may become invaluable “foster parents” for other baby chicks.

In spite of being an SSP-recommended pair, Dunker and Kianga have never had a successful hatching of their own chicks. But Rosenblum says these birds are amazing foster parents, and they have cared for many young chicks over the years. See this couple in Tusher African Hall, identifiable by their red arm bands.

Liz Lindqwister © California Academy of Sciences

Every year, Academy biologists ring in Valentine's Day with a special heart-filled event for our penguins. Gayle Laird © California Academy of Sciences

These young chicks (Alice and Nelson) were born as part of the Academy's penguin baby boom between 2022 and 2023. Gayle Laird © California Academy of Sciences

Steinhart Aquarium is home to nearly 60,000 plants and animals—at least 2,000 of which are fish. Though some are imported from far-off oceans and partner aquaria across the country, the Academy has a Fish Egg Catalog Project that encourages the strategic reproduction of fish in the aquarium and their sustainable collection across the globe. It is part of the Academy’s broader Larval Rearing Program.

As animals who reproduce through a process called broadcast spawning, many of the Academy’s fish will release unfertilized eggs straight into the water column, where these microscopic eggs either fertilize and float—or are left alone to sink and be eaten. Love hurts.

“The egg catalog is so important because it provides data about the complete life cycles of particular animals—it gives you the ability to aquaculture species of interest to an institution,” said Kylie Lev, one of Steinhart Aquarium’s curators. “This reduces the amount of animals you take from wild sources, and we share these resources with other zoos and aquariums.”

In the Fish Egg Catalog Project, researchers collect tens of thousands of eggs from nets dragged over the Philippine Coral Reef's surface. The eggs are photographed and identified by ichthyology staff in the Academy’s Center for Comparative Genomics, which is building a pictorial atlas for other aquaria to understand which fish are actively reproducing.

Gayle Laird © California Academy of Sciences

Sea stars are more than just beautiful aquarium ornaments. By keeping exhibits clean and shifting sands around, these starfish are the “clean up crew” of the ocean, crucial for maintaining the health of aquatic ecosystems. On occasion, tiny sea stars can even be used as food for predator species.

Across the Pacific Coast, sea stars have faced a mass extinction event from the spread of sea star wasting syndrome—a mysterious condition that has killed literally billions of starfish. Because of this, aquariums such as the Academy are invested in growing our own population of bat stars and other protected sea stars.

Working in collaboration with the Henry Doorly Zoo in Omaha, Nebraska, our researchers successfully grew a gaggle of bat stars in 2022—many of which are now on display in the Water Planet exhibit with the Academy’s lumpsuckers (Cyclopteridae).

Bat stars are animals that reproduce out of stress. Environmental factors such as temperature or lunar cycle will send bat stars into a state of crisis, stimulating a broadcast spawning process very similar to that of a coral.

Gayle Laird © California Academy of Sciences

Sunflower stars are incredibly important keystone predators in California’s kelp forest. Sometimes as heavy as 20 pounds—the weight of a hefty watermelon—these massive, multi-armed stars were particularly hard-hit by sea star wasting disease.

“An estimated 90 percent or more of Pycnopodia died during the wasting event,” Lev said. “Our long-term goal is to breed sunflower stars and reintroduce them to the wild—especially at a large enough scale to regrow their population in the Pacific.”

The Academy’s Larval Rearing Program collaborates with several organizations to breed sunflower stars, which are notoriously difficult to reproduce in an aquarium setting. AZA organizations such as the Aquarium of the Pacific, Henry Doorly Zoo, and Birch Aquarium have successfully spawned sunflower stars and are working to raise awareness about their conservation challenges.

The Academy is excited to bring the echinoderm lovefest back to San Francisco this Valentine’s Day, when biologists plan to hold their next sunflower star spawn.

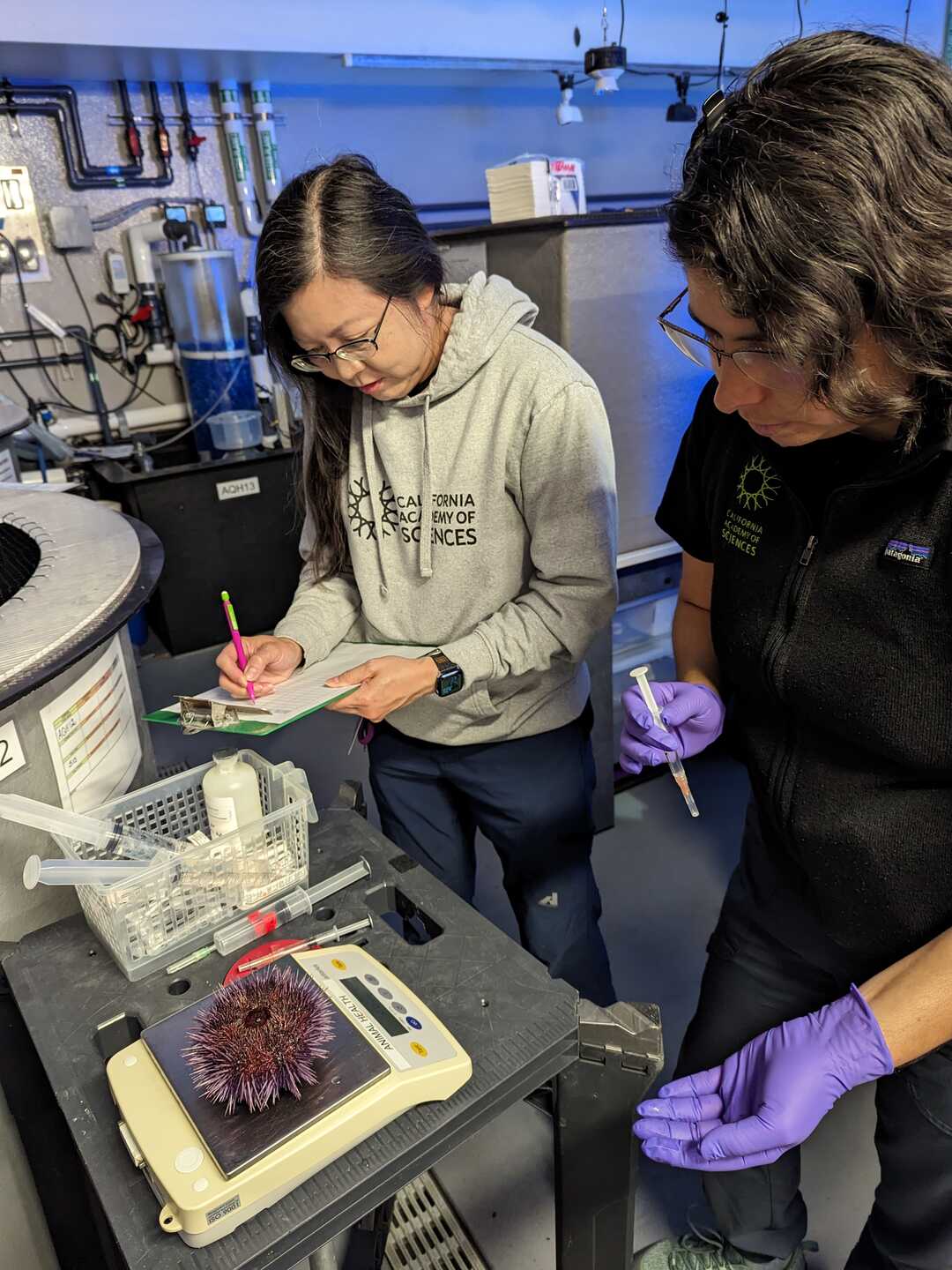

Even the spikiest among us procreate: The Academy also raises several types of sea urchins, another broadcast spawner and keystone species for our aquarium ecosystems. While biologists in the Larval Rearing Program will raise the urchins to adulthood, Academy veterinarians are responsible for helping them reproduce.

“With urchins, they require vigorous shaking or rotating, stimulating the kind of movement they’d naturally get from the ocean’s waves,” said Lana Krol, DVM, an Academy veterinarian. “We do the urchin dance, holding them in our hands and shaking them until the urchins spawn eggs and sperm.”

Urchins in both the California Coast and Philippine Coral Reef exhibits are bred in-house. Lana Krol © California Academy of Sciences

Academy experts help induce urchin spawning by injecting them with a reproductive hormone. Lana Krol © California Academy of Sciences

Monogamous mating. Promiscuous spawning. Efficient asexual reproduction. On display or mysterious. With so many flavors of love at the Academy, there’s an inspiring mood for everyone this season!