The Most Challenging Veterinary Checkup? That’s a Moray

Making sure the thousands of living creatures at the Academy are in strong physical shape is the highest priority for the two veterinarians who are the core of our Animal Health team. From conducting regular checkups on a diverse range of animals to responding to unusual emergencies (a dwarf seahorse C-section and an alligator eating a child’s ballet slipper, to name a couple), no two days—or patients—are alike.

Three species, however, share the same claim to fame: Our moray eels (family Muraenidae), alligator snapping turtles (Macrochelys temminckii), and American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis, aka Claude) are the most difficult to examine We’ll cover the reptiles in future posts; today, it’s all about the eels.

Think it’s hard getting your cat into the carrier for a trip to the vet? Try coaxing a mucus-covered, 20-lb., 50-in. moray eel into a basket. For the Animal Health team, it’s just another day at the office. For starters, “they are slippery,” says Academy Senior Veterinarian Freeland Dunker, explaining why morays are the hardest creature to examine. (To examine electric eels, the vets wear rubber gloves so they don’t get electrocuted. But “I’ve still been zapped,” Dunker says.)

It’s a crisp Wednesday morning when I tag along with the Animal Health team, and it’s immediately clear how much complex choreography is involved in transferring three moray eels from tank to exam table.

First, a diver needs to remove the eels from their exhibit before the Academy opens to the public. After climbing down a ladder into the California Coast habitat, the diver gently maneuvers the eel into a rubber dip net. With the eel in place, the diver then carefully lifts the net out of the exhibit and into a large rolling tank.

After the eels are rolled through the labyrinthine hallways behind the aquarium to the Animal Health department’s exam room, the team quickly gets to work. Speed is important because the water needs to stay at between 59 and 62 degrees for the eels. Ice packs are on hand to help lower the temperature if needed.

Moray eels are hard to tell apart; their sexes can’t even be determined until a necropsy is performed after they die. To confirm who’s who, the team scans each eel with a microchip reader, similar to what is used for a dog or cat, and then records each animal’s identifying features in the Academy’s database. The first one in line for an exam is affectionately known as Fathead; the others have been dubbed Nacho and Long Pretty.

Moray eels await their exam in a portable tank.

A microchip reader identifies each eel.

After the identification, the veterinarians add an anesthetic compound into the water to sedate the eel for the exam. “Basically, they become drunk,” explains Lana Krol, a veterinarian who came to the Academy from the San Francisco Zoo in 2021.

In just a few minutes, the eel has rolled over onto its side in the water, signaling to the veterinarians that it is adequately sedated and ready for the exam: It can still breathe on its own but can now be handled.

“The gills look nice,” Darbi Jones, a veterinary fellow from UC Davis, reports. (Unlike most other fish, moray eels lack opercular gill covers; to breathe, they pass water over their gills by opening and closing their mouths.) She then performs an ultrasound, passing the probe over the eel’s body while looking at the nearby ultrasound screen to see its liver and gallbladder and check its heart rate.

Now it’s time for the tricky part: Removing the animal from the water to weigh it and take x-rays. Lifting a moray eel takes as many as three people—and its smooth, slick skin, protected by a layer of mucus, doesn’t make the job any easier.

Up, up, and a-weigh! The team hefts the eel into a bucket and then puts the bucket onto the scale, deducting the weight of the bucket to calculate the eel’s weight (21 lbs.).

To perform the x-rays, the team carefully places the eel under an x-ray machine and secures it on a foam holder so it stays in place. The soft foam also avoids damaging the eel's delicate skin.

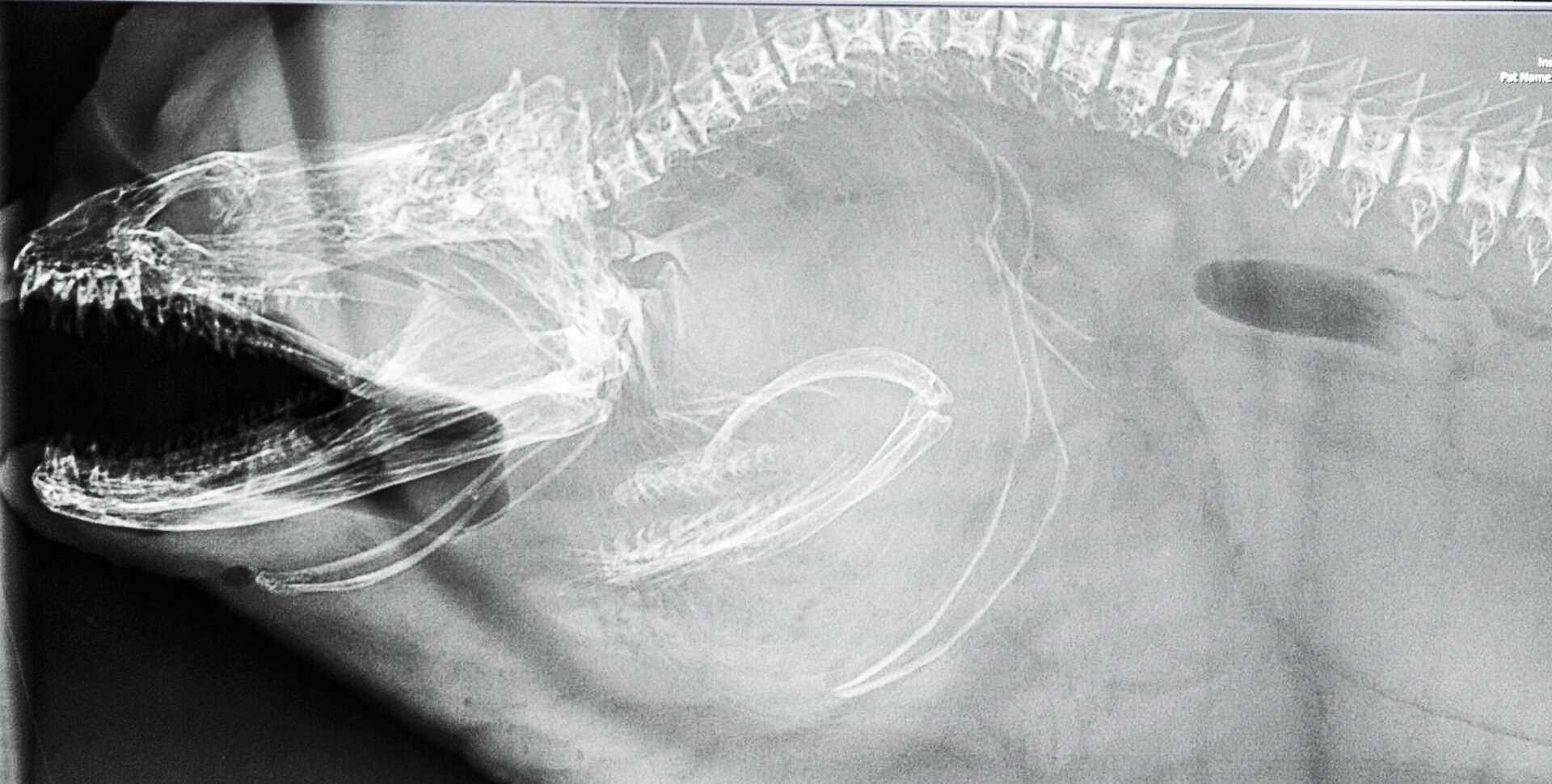

A few clicks later, the x-ray images appear on a laptop, showing the eel’s skull, backbone, and eerie pharyngeal jaw—a second set of jaws that is rumored to be the inspiration for the fearsome "Xenomorphs" from the Alien movies.

"They don't really 'chew' like we do, to make the pieces smaller," explains Krol. "The main jaws are used to capture and hold on to the prey. The pharyngeal jaws in moray eels can actually move forward, which is unusual compared to other fish, and they're used as a secondary way to grip the prey and then move it backwards into the esophagus."

The veterinarians compare the latest x-ray images side by side with images from the previous exams to see if there are any changes, such as evidence of arthritis in the bones or damage to its teeth.

With the x-ray finished, the exam is complete, and the eels are wheeled back to their home in the aquarium. This year they received a clean bill of health and hopefully won’t need another checkup for five years.

"I love eels; they're so cute. They might be my favorite," says Jones. After seeing our morays from all angles, I've come to realize they've slithered their way into my heart, too.