One of the most common questions I get here is why we have so many individual specimens of the same species. It’s a valid question, considering that “collecting,” as far as personal collections go, involves obtaining individuals of a set. What we do here, however, is not like collecting baseball cards; we are essentially a library for researchers to reference when studying a particular organism. In order to have an effective sample size for a study, researchers must look at more than one individual of a species.

The way that we explain this to younger visitors when they come in to tour our collections is: if an alien came into your classroom and wanted to study humans but could only pick two of you as a representation of the entire human species, which ones should the alien take? The students quickly realize that, while they’re all the same species (Homo sapiens), no one person is the “ordinary” example of a human. It’s the same for all species.

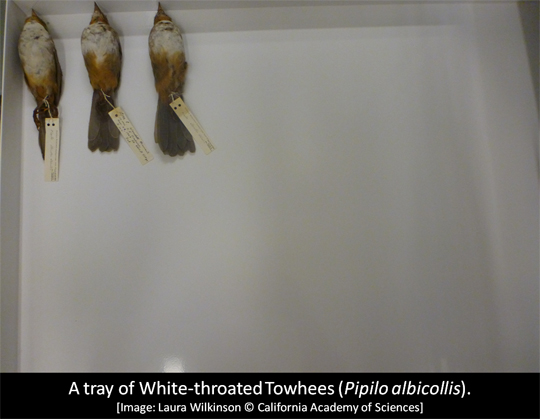

If you were studying a bird species, such as a Towhee, would you prefer to look in a drawer like this:

Or like this?

We clearly have a much larger collection of Collared Towhees than White-throated Towhees. Even though all of these Collared Towhees are the same species, it’s easy to see the variation between each individual. This is why we keep every specimen that is brought to us (given that we know where and what date it was found). Even if not in good enough condition to make a study skin, we can keep the skeleton, a wing, or even the entire specimen stored in ethanol. In fact, we prefer to not make study skins out of every single specimen, or else we wouldn’t have a broad variety of preparations. If a researcher was studying muscle attachments in birds, he/she would want to look at our collection of whole specimens in alcohol. Similarly, if a researcher was interested in studying the leg bones of weasels, he/she would use our skeletal collection instead of study skins.

This is what our collection is all about – having as many reference materials for researchers as possible. Consider how much of research these days relies on DNA and molecular analysis, yet museum curators had no idea about DNA back in the 1800s. Imagine what researchers may be able to do with our research collection 100 years from now that we don’t have a clue about today. It’s exciting to think about how these specimens will be used in the future!

The next time you visit a museum, think about all of the specimens that are kept in collections off of the main floor. While the main floor has a lot of educational material, scientific collections are necessary to further understand life around us.

Laura Wilkinson

Curatorial Assistant and Specimen Preparator

Ornithology & Mammalogy