Scientist Spotlight

Ryan Wyatt

As Senior Director of Morrison Planetarium, Ryan Wyatt oversees the largest all-digital fulldome planetarium in the world that uses real data and revolutionary technologies to transform the way Earth-bound audiences experience the universe.

The big picture

Ryan Wyatt first fell for astronomy as a kid, when his Northern Indiana-based family made a special trip to Chicago’s Adler Planetarium. “That giant projector filled me with a sense of awe,” says Wyatt. “Learning that the Sun wasn’t going to live forever was a horrifying idea to me as a seven-year-old, but it made a huge impression.”

At the start, Wyatt recalls, it wasn’t the aesthetics of the night sky that fascinated him; instead, he was drawn to the larger concepts and theories of the field. “Even as a youngster,” he says, “I sought out a holistic picture. If I learned that a particular star was eight light years away—or a hundred light years away—I’d think about the present moment and how stargazing provides this unique window to gaze into the past.”

That holistic approach can also be seen in the wide range of books that spill from Wyatt’s office shelves, from massive tomes on astrophysics to volumes of ancient mythologies. “In school,” he says, “I was struck by how much detailed information is embedded in these oral traditions. Take the constellation of Taurus, the bull. The Greek myth doesn’t only explain what season or time of day the constellation appears; it’s also a story about a hunt. The story itself provides people with a sense of movement across the sky.”

After earning an undergraduate degree in Astronomy from Cornell University and studying for a Masters in space physics and astronomy from Rice University, Wyatt went on to work for a number of planetariums across the country before settling into a six-year stint as Science Visualizer for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. He joined the Academy in April 2007—just in time to help shape what the new Morrison Planetarium would become.

When art gets real

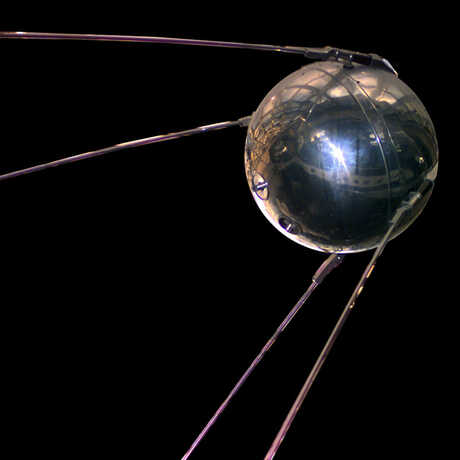

Ryan Wyatt was no stranger to the original Morrison Planetarium. “I had a chance to see that original, unique star projector in action,” he recalls. “[When it was made] in the early ’50s, I don’t think you could have possibly found an artificial star field as glorious as that one.”

Glorious as the old star-projector was, the new Morrison Planetarium needed to be able to transport twenty-first century audiences in ways as magical—and effective—as its predecessor did for those 1950s crowds. Wyatt and the rest of the Academy’s planetarium crew knew that as counter-intuitive as it may sound, nothing’s more breathtaking than cold, hard data.

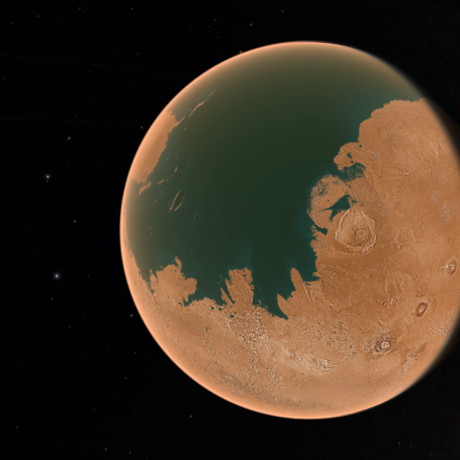

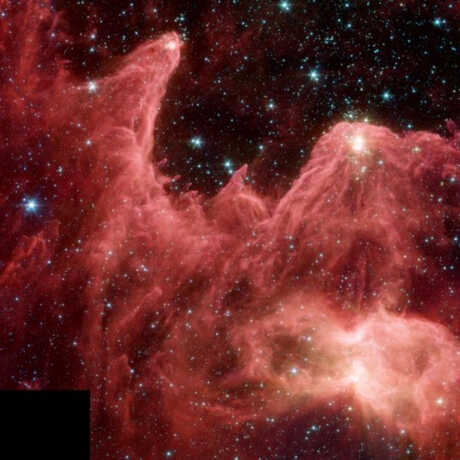

“The most imaginative artist in the world cannot compete with the reality of cosmic phenomena,” says Wyatt—and reality is what Morrison Planetarium-goers get. Start with the largest all-digital dome on Earth, add in talent from the Bay Area special-effects industry, and feed in real data generated by scientific agencies around the world. The result? What Wyatt calls “the biggest storytelling machine” you’ve ever seen.

Thanks to data sets from partners such as NASA, USGS, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratories, and more, every star, supernova, or nebula that Morrison Planetarium audiences fly through is the mirror of a real-life counterpart. And that, Wyatt points out, “meshes perfectly with the Academy’s core function—to present the complex nature of science in all its authenticity.

“Consider how the Academy painstakingly created natural history dioramas in African Hall in the early part of the twentieth century,” he adds. “We strive for the same level of artistry in recreating the natural world of these cosmic environments, except we’re doing it digitally, pixel by pixel.”

Stellar wannabes

In March 2013, Ryan Wyatt accompanied astronomers Jackie Faherty and Chris Tinney to the Las Campanas Observatory in Chile. There, 8,000 feet above sea level in the Atacama Desert, sit the Magellan Telescopes—two of the largest reflecting telescopes in the world.

Wyatt and his colleagues began their night’s work under the light of a nearly full moon, conditions that would have frustrated astronomers who work in the visible spectrum. Faherty, Tinney, and Wyatt, however, were in search of something special: the coldest of all star-like space objects, known as “Y dwarfs.” To hunt them—and to calculate their distance and velocity—you need infrared light.

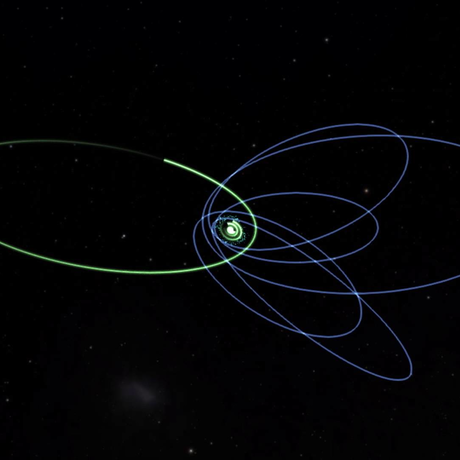

Y dwarfs, a type of brown dwarf, have temperatures that Wyatt describes as “more similar to a human body than a star” and densities that likewise fall short of star status—which explains why Wyatt refers to them as “stellar wannabes.” But it also explains one of the reasons they’re so interesting. Brown dwarfs represent what Wyatt calls “the missing link between giant planets and low-mass stars.”

Calculating Y dwarf locations, ages, and movements through the Universe can tell astronomers a great deal about the composition and evolution of the hundreds upon hundreds of planets we’re finding orbiting other stars. “Each night of observing,” says Wyatt, “plays a role in piecing together a much larger puzzle.”

Universe updates

As the Director of Morrison Planetarium, Ryan Wyatt wears a pretty impressive number of hats. In addition to having written and directed three original, full-length planetarium shows, he’s also the Executive Producer of the Visualization Studio (the in-house Academy production team best known for their interactive floor exhibits) and an international lecturer on astrophysics and science visualization. But put a fulldome canvas at Wyatt’s disposal, and you’ll get something really special.

On the third Thursday of every month, Wyatt’s “Universe Update” combines intellectual rigor, infectious enthusiasm, and a flair for carefully chosen analogies to help planetarium audiences do a cosmic double take. Piloting past a luminous representation of the Magellanic Clouds, for example, Wyatt’s apt to point out, “These are 200,000 light years away from Earth. It would take as long as humanity’s entire evolution to travel there, even at the speed of light.”

Whether he’s discussing the properties of brown dwarf twin stars or planet-protecting spheres of charged particles, Wyatt marvels at the sheer breadth of recent discoveries. “With NASA’s Kepler mission, we’re taking this remarkable survey of more than a 100,000 stars in order to tease out the existence of extra-solar planets,” he says. “It’s radically transforming how we think about what’s going on in space. It’s mind-boggling.”

Department: Planetarium and Science Visualization

Title: Senior Director, Morrison Planetarium and Science Visualization

Videos:

Recreating the Night Sky

The "Special Effects" of Collaborations

Our Place in the Universe

Related websites:

Visualizing Science Blog

"Kitchen Sink" Vitae

The Benjamin Dean lecture series brings the world's leading experts in astronomy, astrophysics, and more to the Academy's Morrison Planetarium.

Stay up-to-date on the latest space-related discoveries and advancements with articles penned by planetarium staff.