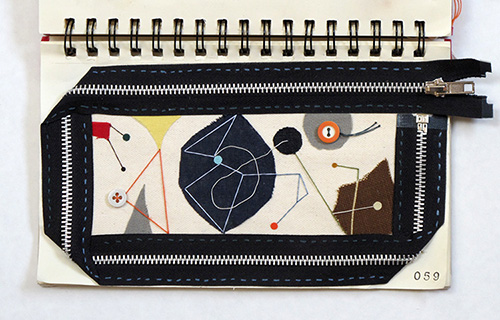

The central element of my new sketchbook page is an abstraction of the constellation Pavo. Visible from Antarctica in the austral winter, Pavo is the 44th largest constellation in the sky and contains five stars with confirmed planets. It is named for Argos of Greek mythology who was transformed into a peacock by the goddess Juno upon his death to be eternally honored as a constellation. Pavo was first depicted in a star atlas in 1603 as part of Uranometria by German celestial cartographer Johann Bayer. In my image, Pavo is flanked by neighboring constellations Triangulus Australe (originally called Triangulus Antarcticus) on the left and Indus on the right, over which a comet passes. The zippered border represents the lifespan of our universe with a defined beginning and end. Astrophysicists at places such as the South Pole's IceCube Neutrino Observatory have long gathered data that adds to our knowledge about the birth and expansion of the universe. But what of its long-term stability? Recent studies of the mass of the Higgs boson subatomic particle, whose discovery was announced at CERN's Large Hadron Collider last year, suggest that the universe may in fact be fundamentally unstable and destined for a catastrophic end. Should this be so, there is no need for immediate concern. The termination of our cosmos is projected to take place tens of billions of years in the future, well after our own sun burns out in 4.5 billion years.

The central element of my new sketchbook page is an abstraction of the constellation Pavo. Visible from Antarctica in the austral winter, Pavo is the 44th largest constellation in the sky and contains five stars with confirmed planets. It is named for Argos of Greek mythology who was transformed into a peacock by the goddess Juno upon his death to be eternally honored as a constellation. Pavo was first depicted in a star atlas in 1603 as part of Uranometria by German celestial cartographer Johann Bayer. In my image, Pavo is flanked by neighboring constellations Triangulus Australe (originally called Triangulus Antarcticus) on the left and Indus on the right, over which a comet passes. The zippered border represents the lifespan of our universe with a defined beginning and end. Astrophysicists at places such as the South Pole's IceCube Neutrino Observatory have long gathered data that adds to our knowledge about the birth and expansion of the universe. But what of its long-term stability? Recent studies of the mass of the Higgs boson subatomic particle, whose discovery was announced at CERN's Large Hadron Collider last year, suggest that the universe may in fact be fundamentally unstable and destined for a catastrophic end. Should this be so, there is no need for immediate concern. The termination of our cosmos is projected to take place tens of billions of years in the future, well after our own sun burns out in 4.5 billion years.