Hello again, I'm back and online at McMurdo after having completed the Field Safety Training Program's Snowcraft 1, popularly known as Happy Camper School. It's a survival training course required for participants going to field camps or day trips, both of which I'm scheduled for next week. My 19 fellow campers and I are now officially prepared to work in the Antarctic environment and to deal (or so we hope) with the possibility of getting caught out in it. Here's how it went...  We began Day 1 at the Science Support Center with an early morning lecture by our two instructors, Danny Uhlmann (above in red shirt) and Jennifer Erxleben. They covered cold weather survival basics including prevention of dehydration, trench foot, UV exposure, snow blindness, hypothermia, and frostbite. Grisly photos of gangrenous digits effectively drove the point home. Then out we went into the glorious weather, as beautiful as an Antarctic day could be, and piled into the passenger pod atop the Delta 2 for our big adventure.

We began Day 1 at the Science Support Center with an early morning lecture by our two instructors, Danny Uhlmann (above in red shirt) and Jennifer Erxleben. They covered cold weather survival basics including prevention of dehydration, trench foot, UV exposure, snow blindness, hypothermia, and frostbite. Grisly photos of gangrenous digits effectively drove the point home. Then out we went into the glorious weather, as beautiful as an Antarctic day could be, and piled into the passenger pod atop the Delta 2 for our big adventure.  January is McMurdo's warmest month. Its average temperature is -2°C / 27°F, allowing folks to pass between buildings in t-shirts. Add some wind chill though and you might suddenly find it at -8°C / 18°F or lower, so we were advised to dress in layers and required to wear our ECW issue clothing for the excursion.

January is McMurdo's warmest month. Its average temperature is -2°C / 27°F, allowing folks to pass between buildings in t-shirts. Add some wind chill though and you might suddenly find it at -8°C / 18°F or lower, so we were advised to dress in layers and required to wear our ECW issue clothing for the excursion.  We were dropped off at Snow Mound City, an area named after the scattered heaps of snow left over from previous training sessions. Mt. Erebus dominated the scenery but the true giant was the Ross Ice Shelf beneath our feet. It is Antarctica's largest ice mass, roughly the size of France. For the next two days, we trained in 8 meters (25 feet) of snow that lies on top of 80 meters (262 feet) of ice that floats over 550 meters (1,800 feet) of water. And all along, we were slowly, ever so imperceptibly sliding out to sea along with Williams Field in the distance, helped along by a neighboring glacier that fed the process. The drifting airfield in fact has had to be relocated three times since its original construction, most recently in 1985.

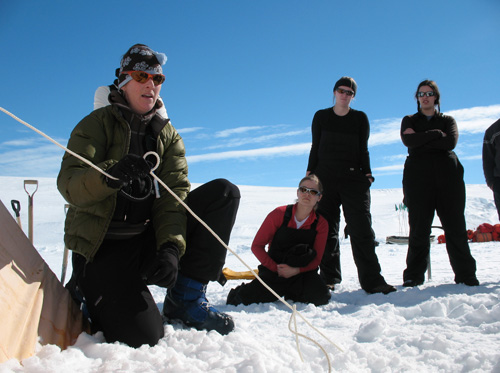

We were dropped off at Snow Mound City, an area named after the scattered heaps of snow left over from previous training sessions. Mt. Erebus dominated the scenery but the true giant was the Ross Ice Shelf beneath our feet. It is Antarctica's largest ice mass, roughly the size of France. For the next two days, we trained in 8 meters (25 feet) of snow that lies on top of 80 meters (262 feet) of ice that floats over 550 meters (1,800 feet) of water. And all along, we were slowly, ever so imperceptibly sliding out to sea along with Williams Field in the distance, helped along by a neighboring glacier that fed the process. The drifting airfield in fact has had to be relocated three times since its original construction, most recently in 1985.  We learned to use and maintain WhisperLite camp stoves, set up tents and secure them with deadman-style anchors, build a quinzhee, dig snow trenches, and saw snow blocks to build structures with. Here Jen demonstrates how to tighten the Scott Polar tent's guy lines using “slippery” knots that release easily when taking the tent back down.

We learned to use and maintain WhisperLite camp stoves, set up tents and secure them with deadman-style anchors, build a quinzhee, dig snow trenches, and saw snow blocks to build structures with. Here Jen demonstrates how to tighten the Scott Polar tent's guy lines using “slippery” knots that release easily when taking the tent back down.  Mountain tents aren't as robust as Scott tents, so they need a snow wall to protect them from the southerly winds. The three layers of blocks went up quite fast owing to our assembly-line technique. It was my first time harvesting a snow quarry with a saw. It's effortless at first but soon becomes a workout -- an extremely fun one.

Mountain tents aren't as robust as Scott tents, so they need a snow wall to protect them from the southerly winds. The three layers of blocks went up quite fast owing to our assembly-line technique. It was my first time harvesting a snow quarry with a saw. It's effortless at first but soon becomes a workout -- an extremely fun one.  We also built a snow galley under Danny's guidance. Here he explains how to best boil down snow to make drinking water and hydrate our freeze-dried dinner packets. Afterwards, he and Jen retired to their Quonset hut a half-mile away, leaving us on our own overnight. As if on queue, snow clouds quickly rolled in to test our mettle.

We also built a snow galley under Danny's guidance. Here he explains how to best boil down snow to make drinking water and hydrate our freeze-dried dinner packets. Afterwards, he and Jen retired to their Quonset hut a half-mile away, leaving us on our own overnight. As if on queue, snow clouds quickly rolled in to test our mettle.  It snowed throughout the night, heavily at times. Still, it didn't deter the most industrious of our bunch from digging themselves all manners of snow trenches to sleep in.

It snowed throughout the night, heavily at times. Still, it didn't deter the most industrious of our bunch from digging themselves all manners of snow trenches to sleep in.  I'd love to say I slept in my own snow shelter, but my heart was equally set on sleeping in the Scott Polar tent, the standard Antarctic exploration shelter for almost 80 years. It's basically the same kind that Robert Falcon Scott himself used, a tent so sturdy that it remained standing throughout the winter long after he and his men perished on their trek back from the South Pole.

I'd love to say I slept in my own snow shelter, but my heart was equally set on sleeping in the Scott Polar tent, the standard Antarctic exploration shelter for almost 80 years. It's basically the same kind that Robert Falcon Scott himself used, a tent so sturdy that it remained standing throughout the winter long after he and his men perished on their trek back from the South Pole.  Perhaps it's easy to say from a cozy Scott tent, but it was special experiencing snowfall in Antarctica, which gets so little precipitation. Even the coast, which receives the most snow of the continent, qualifies as a desert. Why so much snow on the ground then? Because unlike other deserts, there's little evaporation, allowing hundreds and thousands of years' worth of light snowfalls to accumulate into enormously thick ice sheets. It felt like somewhat of a privilege to witness a fraction of that build-up.

Perhaps it's easy to say from a cozy Scott tent, but it was special experiencing snowfall in Antarctica, which gets so little precipitation. Even the coast, which receives the most snow of the continent, qualifies as a desert. Why so much snow on the ground then? Because unlike other deserts, there's little evaporation, allowing hundreds and thousands of years' worth of light snowfalls to accumulate into enormously thick ice sheets. It felt like somewhat of a privilege to witness a fraction of that build-up.  We're on Day 2 now. Danny and Jen returned to find us alive and sleep-deprived. We broke camp and congregated at the Quonset hut for lunch, a de-briefing, risk-management lecture, and HF / VHF radio training, after which we went back out for our simulation exercises. Danny led us in a plane crash scenario which called for putting all the skills we'd learned into practice and work as a team to survive in the field.

We're on Day 2 now. Danny and Jen returned to find us alive and sleep-deprived. We broke camp and congregated at the Quonset hut for lunch, a de-briefing, risk-management lecture, and HF / VHF radio training, after which we went back out for our simulation exercises. Danny led us in a plane crash scenario which called for putting all the skills we'd learned into practice and work as a team to survive in the field.  Jen hosted the final field program, the infamous buckethead exercise which simulates a total white-out situation -- zero visibility -- to conduct a search-and-rescue in. We failed to find the "lost" person, but as Jen later revealed, team-building, communication and planning were the most important aspects of this exercise. In which case, we did quite well.

Jen hosted the final field program, the infamous buckethead exercise which simulates a total white-out situation -- zero visibility -- to conduct a search-and-rescue in. We failed to find the "lost" person, but as Jen later revealed, team-building, communication and planning were the most important aspects of this exercise. In which case, we did quite well.  Snowcraft wrapped up back at McMurdo with videos on helicopter safety and working in the Dry Valleys. Then we were free to go; exhilarated, exhausted, and primed for our upcoming trips within the continent. The course was the highlight of my stay so far, and an experience I'll never forget. It's very cool to have acquired these outdoor survival skills, and inadvertently an indoor one too: surviving 48 hours without internet access.

Snowcraft wrapped up back at McMurdo with videos on helicopter safety and working in the Dry Valleys. Then we were free to go; exhilarated, exhausted, and primed for our upcoming trips within the continent. The course was the highlight of my stay so far, and an experience I'll never forget. It's very cool to have acquired these outdoor survival skills, and inadvertently an indoor one too: surviving 48 hours without internet access.  The full cast as photographed by fellow Happy Camper David Argento. Thanks Dave!

The full cast as photographed by fellow Happy Camper David Argento. Thanks Dave!