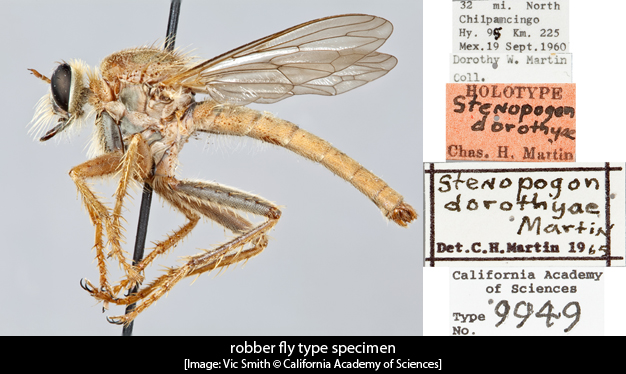

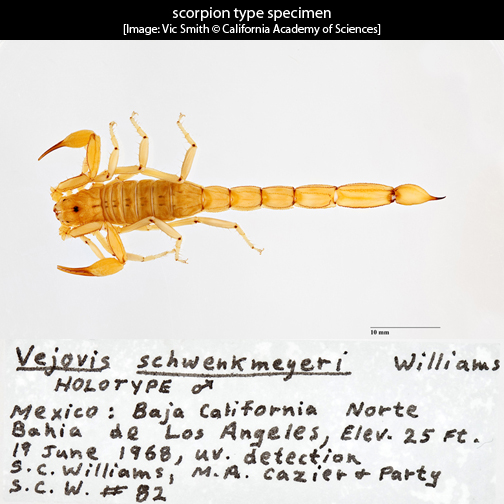

One of the important jobs taking place in the Project Lab is the imaging of specimens from the Academy’s type collection. Over the past several years I have been actively working to photograph some of the Academy’s type specimens of insects and arachnids, and other workers have been documenting type specimens of reptiles, amphibians and fish. The Entomology Department alone has about 18,000 type specimens, of which only a small fraction has been imaged (good job security for me!).

So, what is a type specimen, and why are they important?

When a researcher thinks they have found an undescribed and unnamed species, the first thing they have to do is make sure that it hasn’t already been named. This can be quite a problem in itself, as much of the scientific exploration of the world took place from the mid 1700’s to the late 1800’s, when sovereign nations sent out explorers in ships to find out what was in the world. These folks did not have iphones, the internet, or even a postal system with which to communicate, and as a consequence, many species got described and named multiple times. According to the rules established by the international committee on species naming, it is the earliest published description that has the valid name. Fortunately, today, we do have the internet and phone resources that allow us to do the detective work to determine if the species is undescribed.

Once the researcher has determined they are working with a new species, they will go through the process of carefully describing the organism, paying special attention to the similarities and differences between the new species and all known similar species, and noting the characteristics that make it distinct from all other species. They will also place the new species within a taxonomic hierarchy, such as order, family, and genus.

This description is then submitted for review by anonymous peers, who evaluate the work and suggest strengths and possible weaknesses for revision. Once evaluation and revision are completed, the paper may be accepted for publication, and a new species has been officially named and recorded! But, there is one more step to make the process complete and official. The researcher must designate a type specimen called a holotype. This is often the specimen from which the description was actually made. The holotype serves as the placeholder for the species name, and is deposited in a museum like the California Academy of Sciences. Because there is only one holotype for each species, different museums all around the world have different holotypes in their collections.

These holotype collections are of great importance to researchers, who often compare the named types to specimens they are working on, to see if they have found new species. It is the responsibility of museums like ours to make these type specimens available to researchers, and in the past, the only way to share was by sending out the actual specimen. This always involved a certain amount of risk on the part of the lender, with the possibility that the specimen would be retained, lost, damaged or destroyed in transit. By taking a series of high quality images that show the important features of the organism, as well as recording the original labels, it is often possible to give researchers the information they need without having to send the specimen. In addition, all of these photographs will be posted on the Academy website, where they are viewable to the public (Entomology Types). At present, our collection of robber flies, (family Asilidae), and our types of scorpions are available on the web, as well as Coleoptera (beetle) types. Our entire collection of spider types is soon to be completed, and some of the other insect orders have spotty representation as images.

Now it is time for me to get back to work creating images, so until next time…

Vic Smith

Curatorial Assistant and Imaging Specialist.