This week, May 7th to May 13th, the Academy of Sciences celebrates International Migratory Bird Day. Although it was originally slated as the second Saturday in May, the birds don’t always recognize our time schedule, and in some places, migratory birds had already left the area so the single day celebration was extended to an entire week.

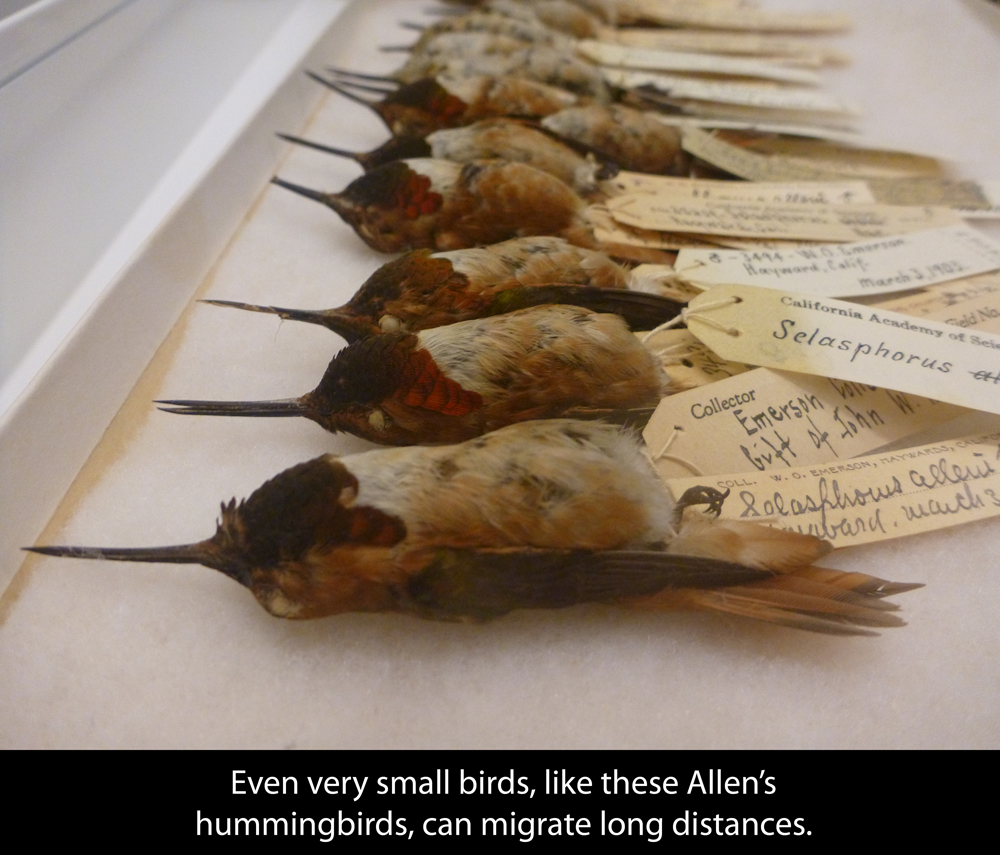

Here at the Academy, the Ornithology and Mammalogy department's research collection aids researchers in studying bird migration. Often times migration can be shrouded in mystery-exact migration routes of species can be little known or unknown altogether! By analyzing stable isotopes, or chemical compounds, in feathers of our study skin collection, researchers can determine geographical locations visited by the migrating birds on their long flight. But why migrate at all?

Many birds use migration as a tactic to ensure secure food supplies all year round, especially around breeding time. Generally, in the Northern Hemisphere, birds will fly north to more temperate spring/summer breeding grounds and then head back down south when winter approaches their northerly breeding habitat. This allows them to take advantage of warm weather year round, effectively securing their food source consistently for their own stomach and the young they raise. Some migration journeys take months and some take days depending upon the distance and flight of the bird.

Arctic Terns have one of the longest distances to travel of any birds; they travel 12,000 miles from Antartica in the southern hemisphere’s summer to their Arctic breeding grounds during the northern hemisphere’s summer. This journey from pole to pole takes this 13-inch bird only a few months to complete!

Instead of migrating for a few months, Bar-tailed Godwits migrate in a little over a week. This is despite the fact that Bar-tailed Godwit has one of the longest continuous migrations. They often journey 11,000 miles from New Zealand to their breeding grounds in Alaska in one trip. A trip to Hawaii from San Francisco is around 2300 miles. Imagine flying to Hawaii and back four and a half times without stopping!

These long migrations are not limited to larger birds either. Allen’s hummingbirds also migrate from parts of Southern Mexico up the coast to southern California, a trip of 1500-2400 miles!

For all birds, migration can be a dangerous, exhausting time. Since one of the driving factors is food, some birds choose not to migrate if they are fed all year round by an outside source like bird feeders or if they land somewhere that has a temperate climate all year. Some hummingbirds will choose to stick around if they have access to bird feeders and a subspecies of one of our San Francisco residents, the White-crowned Sparrow will not migrate and choose to breed along the coastline.

Bird migration is a truly awesome feat of stamina! Come check out the Project Lab during Migratory Bird week for some specimens of migratory birds on display. We also will be having specimen preparation during Nightlife on May 10th as well as our collections manager, Maureen Flannery, discussing bird migration!

You can also visit the official International Bird Day website here: http://www.birdday.org/birdday.

Codie Otte

Curatorial Assistant and Specimen Preparator

Ornithology & Mammalogy Department