Snakes are not great over-ocean dispersers; they are certainly better than frogs or freshwater fish but not as successful as spiders, geckos and skinks. For instance there are no native snakes in the Hawaiian Islands although they do occur in the Galapagos, but these are much closer to a source continent. In spite of their small size and isolated nature, and Príncipe have a rather surprising snake fauna; there are at least seven species, five of which we know to be endemic - they are found nowhere else. This group includes three species of “lower snakes” or scolecophidians; these are small, blind burrowing forms, two of which are endemic to São Tomé and one to Príncipe.

Rhinotyphlops newtonii, a burrowing scolecophidian from Sao Tome. (D. Lin phot. GG I)

The more advanced snakes (caenophidians) are represented by one endemic, diurnal (daytime) species on each island (belonging to two unrelated genera) and a nocturnal subspecies which is currently thought to be the same on both islands.

Hapsidophrys principis- (cobra sua sua:“snake fast”)- the endemic diurnal species of Principe (D. Lin phot. GGI).

The nocturnal snakes are known as cobra jita (“snake slow”). I have mentioned these in earlier blogs, and my suspicions are that the two island populations are distinct endemics—we are beginning a molecular study this summer to test this hypothesis.

Cobra jita ("snake slow"), the nocturnal species from both islands? (Weckerphoto. GG III)

But here I want to talk about the remaining snake found on São Tomé which the islanders call cobra preta (“snake black”); this is the only dangerous species on the islands, and it is a bit of a mystery to me.

The black and white, or Forest cobra - Naja melanoleuca. Ethnobiomed phot.

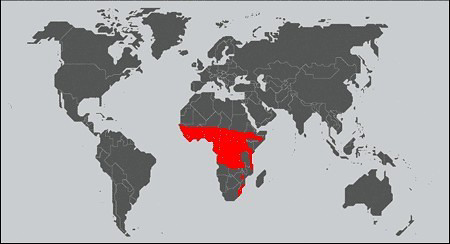

Widely distributed on the African mainland, this species is known as the forest cobra, or black and white cobra (Naja melanoleuca), and it is quite a venomous and formidable animal. In some parts of its range it can exceed 3 meters in length (10’).

Forest cobra distribution. map by Nils Boyson

Head of Forest or Black and White cobra, Naja melanoleuca.

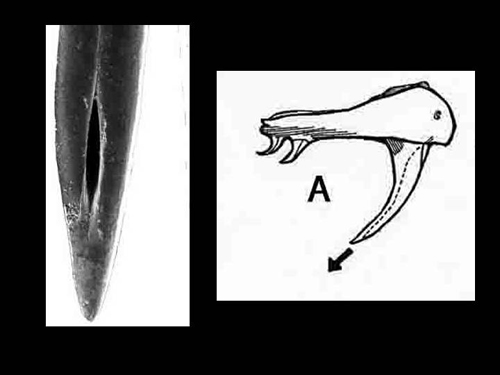

This snake, like most true cobras, displays a hood as part of its defense system, essentially making itself look larger in order to warn of its presence. Like all members of family Elapidae, cobra preta has erect front fangs that are hollow and syringe-like, and it injects prey animals with venom that attacks the nervous system (neurotoxin).

[l.] C. melanoleuca fang showing aperture (Bruce Young) [r.] direction of venom injection (E. Jose)

All of the São Toméans know of cobra preta and fear it, although I have no idea how frequently citizens are bitten. Based on a dead-on the-road specimen at nearly sea level in the south of the island, we know it occurs in lowlands, but I suspect it is more common in the mid-level forests; during GG I, we purchased a number of skins from farmers at Bombaim, which is at middle elevation.

Dead on the road, south Sao Tome. (RCD phot. GG recon 2000)

Joel Ledford with Bom Sucesso specimen. (J. Ledford phot. GG I)

The 2- meter specimen above was killed by locals near the Botanic Gardens and Herbarium of Bom Sucesso at about 1000 m, and we were able collect it during the GG I expedition.

During GG II in 2006, we encountered a very large specimen while collecting along an aquaduct in the Contador Valley on the west side of the island at 700 m; in fact, several of us nearly stepped on it before we were aware of its presence.

On our most recent foray, GG III A, we were again on the Contador Aquaduct when a middle-sized snake was killed by locals around a bend in the road, less than 100 m from where we were working.

Contador Valley specimen (Weckerphoto GG III)

Regrettably, they had beheaded the specimen, and so it was of no value as a voucher specimen; however, we were able to photo-document the animal and I removed some liver tissue for future analysis.

Liver tissue removal. (Weckerphoto. GG III)

The presence of the cobra on São Tomé Island is widely considered to be the result of human introduction, most likely accidental (it is hard to imagine an individual bringing a deadly snake on purpose!). Physically it appears to be identical to the widespread Naja melanoleuca of the mainland. Accidental introduction makes ecological sense to me as well because the species does not really fit into this old ecosystem as we are beginning to understand it. We know that the other higher snakes feed on endemic prey species such as frogs and lizards. But aside from some birds, there do not seem to be endemic prey species that are of sufficient size to sustain a large, heavy-bodied snake like cobra preta; on the other hand, plenty of rats, chickens, etc. have been brought over by humans since the 15th Century.

Two of the top African cobra experts are Drs Wolfang Wuster of the University of Wales and Donald Broadley of Zimbabwe. They are currently working on this species, and we have been sending them our tissue samples for DNA analysis. Soon, we should know whether or not this large cobra drifted out to the islands on its own and has since been genetically diverging, or whether it was brought to the island through human agency. Wuster and Broadley are currently describing a new species from Ghana that was long thought to be the species Naja melanoleuca.

Our parting shot:

Roadside enterprise on Principe(Weckerphoto GGIII)

PARTNERS

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the G. Lindsay Field Research Fund, Hagey Research Venture Fund of the California Academy of Sciences, the Société de Conservation et Développement (SCD) for logistics, ground transportation and lodging, STePUP of Sao Tome http://www.stepup.st/, Arlindo de Ceita Carvalho, Director General, and Victor Bomfim, Salvador Sousa Pontes and Danilo Bardero of the Ministry of Environment, Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe for permission to export specimens for study, and the continued support of Bastien Loloumb of Monte Pico and Faustino Oliviera, Director of the botanical garden at Bom Sucesso. Special thanks for the generosity of private individuals, George F. Breed, Gerry F. Ohrstrom, Timothy M. Muller, Mrs. W. H. V. Brooke and Mr. and Mrs. Michael Murakami for helping make these expeditions possible.