The Race: The Amphibians of Sâo Tomé and Príncipe, and the Eighth Expedition

The Biodiversity Education team has been hard at work on our product for GG VIII, of April, 2014. The 2000 students we have been visiting since the 3rd grade are now in the 5th grade and will be moving on next year, so this is our last visit with them. We have produced a slightly more technical biodiversity booklet (livreto) for each of them. This cohort represents slightly more than 35% of the island studentsin their age group.

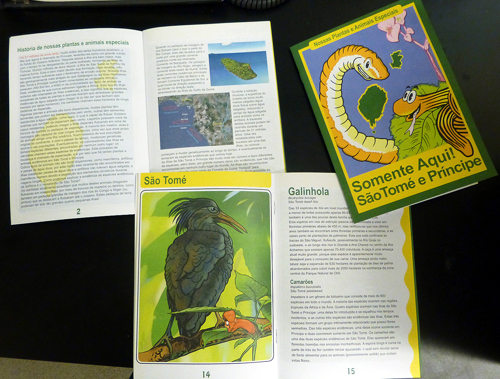

NOSSAS PLANTAS E ANIMAIS ESPECIAIS.

The Bio-education team in my Lab: Roberta Ayers (senior educator, and translation - on Skype), Velma Schnoll (Project Manager), Lindzy Bivings (education advisor),Jim Boyer (art work and layout), Tom Daniel (science text).Absent: Mike Murakami (graphics), me..

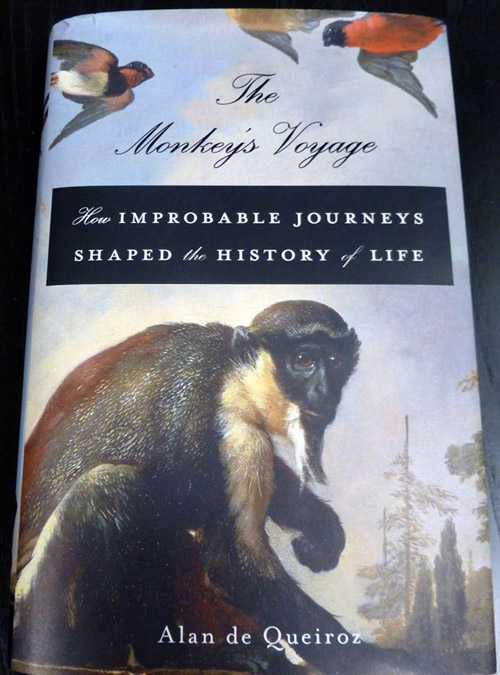

Just recently a great new book was published called The Monkey’s Journey, by Alan de Queiroz. An entire chapter (6) is based on our hypothesis as to how amphibians and many of the other unexpected, endemic animals originally crossed over to the islands from the mainland.

One of us has made an exciting discovery recently (see below) which prompts me to reacquaint readers with the amazing amphibian fauna of Sâo Tomé and Príncipe. As readers already know, there should not be any amphibians on these islands at all; they are true oceanic islands which have never been attached to the African mainland, and amphibians have no tolerance for saltwater. There are no native amphibians on the Galapagos or the Hawaiian Islands for this reason. Yet, there are seven species on our islands, possibly eight – all unique and found nowhere else in the world! The most unlikely of these is the famous “Cobra bobo” of Sâo Tomé.

Cobra Bobo in the hands of Quintino Quade of Sao Tome. D. Lin phot - GG I

Upper left, unknown phot, upper right, RCD GGI, lower, R. A. Nussbaum

The cobra bobo (Schistometopum thomense) is a caecilian, part of a group of amphibians only distantly related to frogs and salamanders. They are found almost exclusively in the Old and New World Tropics. About 25% of the 200 species lay eggs, the rest, including our cobra bobo give birth to living young (see above).

Although they look very much like earthworms, caecilians have backbones, teeth and a vertebral columns. (above lef-UCL photot). Most are burrowers although some are aquatic, but all caecilians lack legs, tails and have reduced eyes, and they are the only amphibians that have sensory tentacles located on each side of the head, between the nostril and the eye (above right – different species-J. Measey phot.). These are protruded to sense prey items and the environment.

The cobra bobo is widespread under moist leaf litter, old banana stems, etc from sea level to as high as 1400m, at Lagoa Amelia. Although they are totally harmless, they are widely feared by the islanders, which is the reason we use a cobra bobo cartoon for our expedition logo (see earlier posts). We are attempting to demystify it. One of the most interesting things about this endemic species is the distribution of its closest relative.

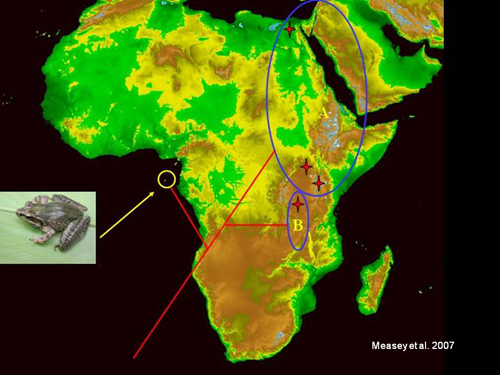

Note that several thousand km separate the two known species; the red ? indicates a single old specimen in Brussels from the Ituri region of Zaire that might also be a member of the same genus.

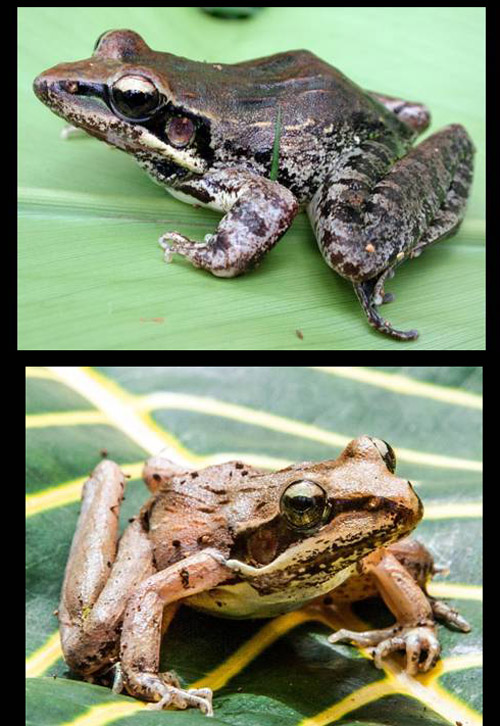

A frog unique to Sâo Tomé is Newton’s rocket frog, Ptychadena newtoni. There are over 50 species recognized on the African mainland, but this endemic is by far the largest of the genus, with females attaining lengths of over 60mm. This qualifies Newton’s rocket frog as a true “island giant.”

Newton's rocket frog. above phot RCD- GGI, below A. Stanbridge,-GGVI

Early records suggested it is a frog of streams and rivers in the northern lower elevations, but we have found its larvae as high as Java, at 600m, and in recent years, Hugualay Maya of ABS has discovered the species in river drainages farther south down the west coast. (pink markers).

Known localities for Newton's rocket frog. RCD construct

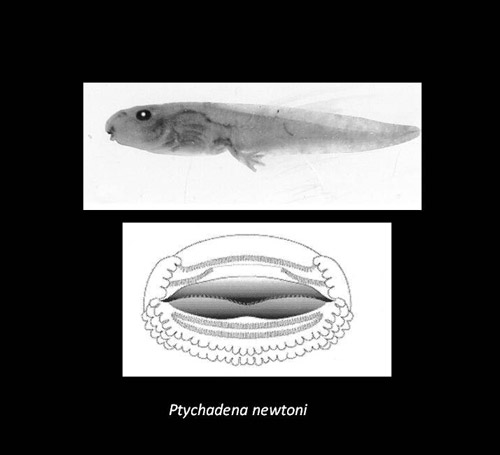

Frog larvae (or tadpoles as they are often known in English) are used in identification of species by scientists, as well as the study of adults and are formally described.

Ptychadena newtoni. above, whole larva; below are mouthparts] drawings -Dylan Kargas.

An extremely interesting fact about Newton’s rocket frog is the location of its closest relatives. Like the cobra bobo, the species of Ptychadena genetically closest to our island frog are eastern species, not Central or West African.

This study included 108 rocket frog samples from all over sub-Saharan Africa, including the Nile drainage, Madagascar and the Seychelles.

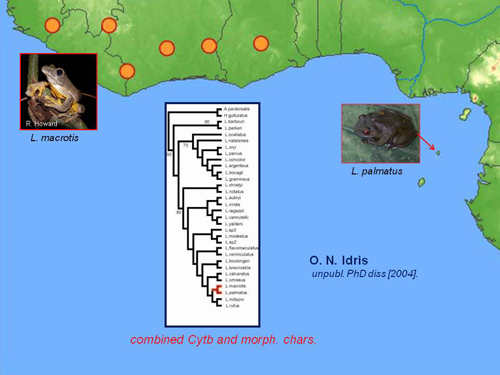

Another endemic island giant is Príncipe’s giant treefrog, Leptopelis palmatus. In fact, the first specimen ever collected and described nearly 150 years ago was a female measuring 110mm from snout to between the legs. This is the largest ever recorded for the genus. The largest specimen we have collected was a 108mm female, during GG I near Sundi.

Sundi female of 108mm. D. Lin phot-GG I

Left: same female, R Stoelting phot. GG I; right: Pico Papagaio male, just after calling. Weckerphoto GG III

There are a number of strange things about this species; the females are usually always dark to dull green, while the males come in a great range of color patterns, some quite bright (polychromatic- see below). Moreover, the largest males are usually less than half the size of the females (above and below). While we were the first to record its call, this is the one species on both islands for which we have no data for eggs or larvae. Most large females have been found in the lowlands of Príncipe, while males seem to be common up to 700m on the Pico.

Three males and a juvenile Principe giant tree frog. J. Ledford phot- GG I

Distribution of the Príncipe giant tree frog and its closest mainland relative, L. macrotis. This may suggest that the ancestor of both rafted from the Niger River delta into the Gulf of Guinea.

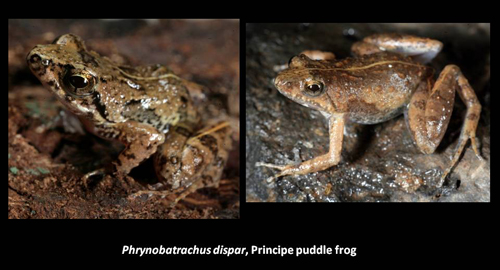

Both islands have small species of puddle frog, Phrynobatrachus, that are widely distributed on both islands in leaf litter, and breed in temporary puddles of water. Both island forms were thought to be the same species (they are tiny and remarkably similar to the untrained eye) until we discovered that they were genetically quite distinct species with physical differences.

The Príncipe puddle frog, Phrynobatrachus dispar, can be found in wet areas from sea level to the top of Pico do Príncipe. While we have its larvae and eggs, we have not yet described them. D. Lin phots-GG II.

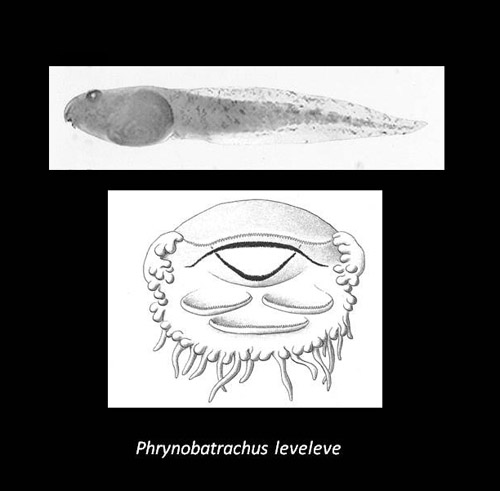

The Sao Tome puddle frog, Phrynobatrachus leveleve is very similar in appearance to the Príncipe species but there are great genetic differences and physical differences as well. Like its relative on Príncipe, it is broadly distributed in wet areas from sea level to very high elevations. RCD phots, GG VI.

Its larval characteristics can be seen below.

Drawings: Dylan Kargas

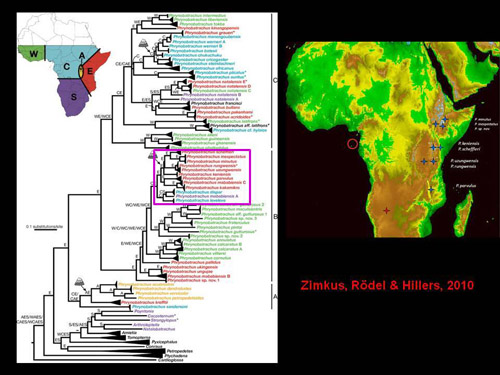

Like the other amphibians, the distribution of the nearest relatives of our two island puddle frogs is intriguing.

According to a recent study, Príncipe’s puddle frog, P. dispar is most closely related to a population in the Caprivi Strip of Namibia, and together their nearest relative is P. leveleve of Sâo Tomé. The interesting thing to notice is that all of the other members of this lineage, called a clade and defined by the purple box, are East African species. This is reminiscent of the rocket frog and cobra bobo distributions.

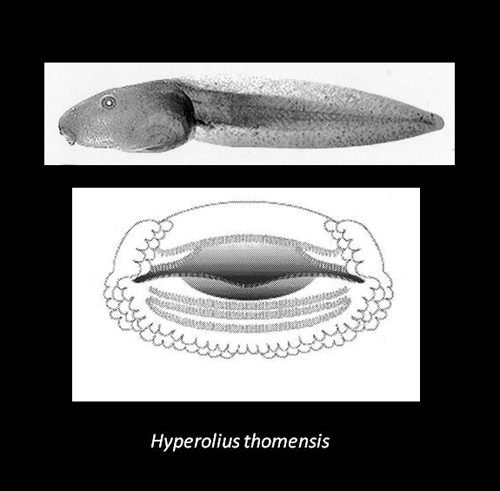

Returning to island giants, we have the Sâo Tomé giant treefrog, Hyperolius thomensis. There are well over 200 species of this genus known from the African mainland, and females of this Sâo Tomé endemic are by far the largest at just under 50mm.

D. Lin phot- GG I

D.Lin phot. GG - I

Breeding pair of Sao Tome giant treefrog. D. Lin phot, GG II

This large flamboyant tree frog appears to largely be a tree canopy dweller. We have discovered that eggs are laid in water-filled holes in trees (phytotelmata). They can be heard calling from treetops but are extremely difficult to locate; in fact all of our specimens have come from a single locality at around 1100m; we monitor this locality every year and keep its exact location a secret. We have described the larval characteristics, below.

Drawings by Dylan Kargas

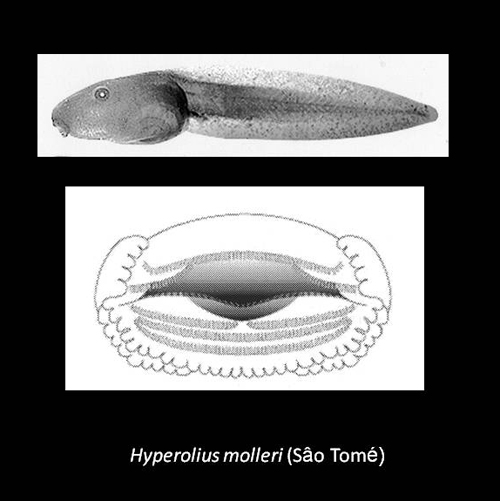

Our last endemic species is closely related to the Sâo Tomé giant tree frog, although it is much smaller and not so brightly colored: Hyperolius molleri, the oceanic tree frog. Since our work began, it is the only remaining amphibian that has been thought to inhabit both Sâo Tomé and Príncipe. In fact, years ago an early intern of mine, Katie Marshall, compared the two populations using mitochondrial genes and found no significant differences between them; they are certainly extremely similar morphologically ( see below).

Above, Weckerphoto GG III; below, RCD phot GG I

Recent work by Rayna Bell, our Cornell colleague (GG VI, VII) included a reanalysis of the two populations with more advanced technology, and indications are that the two populations may be quite distinct genetically. If this turns out to be the case, the Príncipe population will require much closer morphological examination and redescription, bringing the total number of endemic amphibians on our islands to eight!

While this small green tree frog appears to be a lower elevation dweller on Príncipe, on Sâo Tomé it reaches at least 1400m and can be heard calling at Lagoa Amelia. Like most other members of the genus, eggs are laid on leaves above water, the developing tadpoles ultimately wiggling out of the jelly mass and falling into the water for further development. We have studied the larvae of the big island form (the original Hyperolius molleri- the species was described based on a specimen from that island) and the characteristics are below.

Drawings by Dylan Kargas

The team leaves for the islands in early April; our mission for GG VIII will largely be on biodiversity education as I mentioned in the beginning, but we will continue to post on our progress while there.

Until then, here is the parting shot:

The brilliant Blue-breasted kingfisher of Principe Island. Photo by Michael "Bobby" Bronkhorst, 2014

PARTNERS

We are most grateful to Arlindo de Ceita Carvalho, Director General, Victor Bomfim, and Salvador Sousa Pontes of the Ministry of Environment, Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe for their continuing authorization to collect and export specimens for study, and to Ned Seligman, Roberta dos Santos and Quintino Quade of STePUP of Sao Tomehttp://www.stepup.st/, our “home away from home”. We gratefully acknowledge the support of the G. Lindsay Field Research Fund, Hagey Research Venture Fund of the California Academy of Sciences for largely funding our initial two expeditions (GG I, II). The Société de Conservation et Développement (SCD) and Africa’s Eden provided logistics, ground transportation and lodging (GG III-V), and special thanks for the generosity of private individuals who made the GG III-V expeditions possible: George G. Breed, Gerry F. Ohrstrom, Timothy M. Muller, Mrs. W. H. V. Brooke, Mr. and Mrs. Michael Murakami, Hon. Richard C. Livermore, Prof. & Mrs. Evan C. Evans III, Mr. and Mrs. Robert M. Taylor, Velma and Michael Schnoll, and Sheila Farr Nielsen; GG VI supporters include Bom Bom Island and the Omali Lodge for logistics and lodging, The Herbst Foundation, The “Blackhawk Gang,” the Docent Council of the California Academy of Sciences in honor of Kathleen Lilienthal, Bernard S. Schulte, Corinne W. Abel, Prof. & Mrs. Evan C. Evans III, Mr. and Mrs. John Sears, John S. Livermore and Elton Welke. GG VII was funded by a very generous grant from The William K. Bowes Jr. Foundation, and substantial donations from Mrs. W.H.V.“D.A.” Brooke, Thomas B. Livermore, Rod C. M. Hall, Timothy M. Muller, Prof. and Mrs. Evan C. Evans, Mr. and Mrs. John L. Sullivan Jr., Clarence G. Donahue, Mr. and Mrs. John Sears, and a heartening number of “Coolies”, “Blackhawk Gang” returnees and members of the Academy Docent Council. Once again we are deeply grateful for the continued support of the Omali Lodge (São Tomé) and Bom Bom Island (Príncipe) for both logistics and lodging and especially for sponsoring part our education efforts for GG VII and GG VIII. Substantial support has already come in for our next expeditions from donors in memory of the late Michael Alan Schnoll, beloved husband of our island biodiversity education Project Manager, Velma.

Our expeditions can be supported by tax-deductable donations to “California Academy of Sciences Gulf of Guinea Fund”