The Lobster by Douglas Florian

See the hard-shelled leggy lobster

Like an underwater mobster

With two claws to catch and crush

Worms and mollusks into mush

And antennae strong and thick

Used for striking like a stick

So beware when on vacation

Not to step on this crustacean

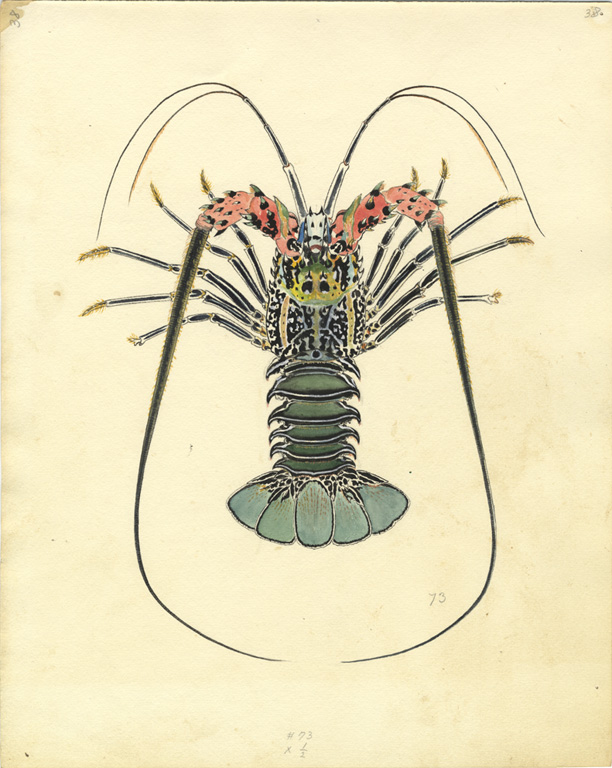

Spiny lobsters have two noticeable anatomical differences from the more well known Maine lobster. First are the thickened spiny antennae (hence the common name). Secondly, the first set of walking legs do not end in enlarged chelipeds (or claws). The Japanese spiny lobster, Panulirus japonicus, lives off the coast of Japan, Korea and China. Many restaurants will have it labeled Ise Ebi. It is similar in appearance to the California spiny lobster, Panulirus interruptus.

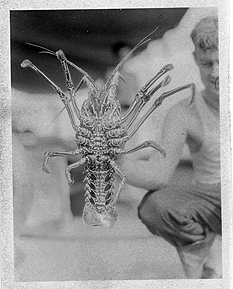

Asaeda, Toshio. Panulirus Japonicus, Thai Lagoon, Malaita. May 31, 1933. ©California Academy of Sciences Archives, San Francisco, CA.

This image is a part of Toshio Aseada’s collection housed here at the California Academy of Sciences Archives. Gifted in the arts of painting, photography, and taxidermy, and educated in geology, zoology, botany, and geography, Mr. Aseada found work at the California Academy of Sciences beginning in 1927 as an artist for the Academy’s ichthyology department. Asaeda accompanied Templeton Crocker and Academy scientists on several scientific expeditions, including a 1933 trip to the Solomon Islands. Because specimens lose their pigmentation quickly when preserved in formalin and other aqueous solutions, Asaeda was tasked with painting the specimens when they were collected in order to capture their brilliant colors. This specimen was captured in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of the island of Malaita and drawn from life. Reproductions of some of Aseada’s specimen illustrations are on display on the California Academy of Sciences’ main floor in the Islands of Evolution exhibit.

For me, this species was more difficult to research. Not only was I unable to get hold of a live lobster, but the literature was either highly specialized (Spiking induced by cooling the myocardium of the lobster, Panulirus japonicus) or very broad (Marine Lobsters of the World, QL444.M33 H658 1991 Main).

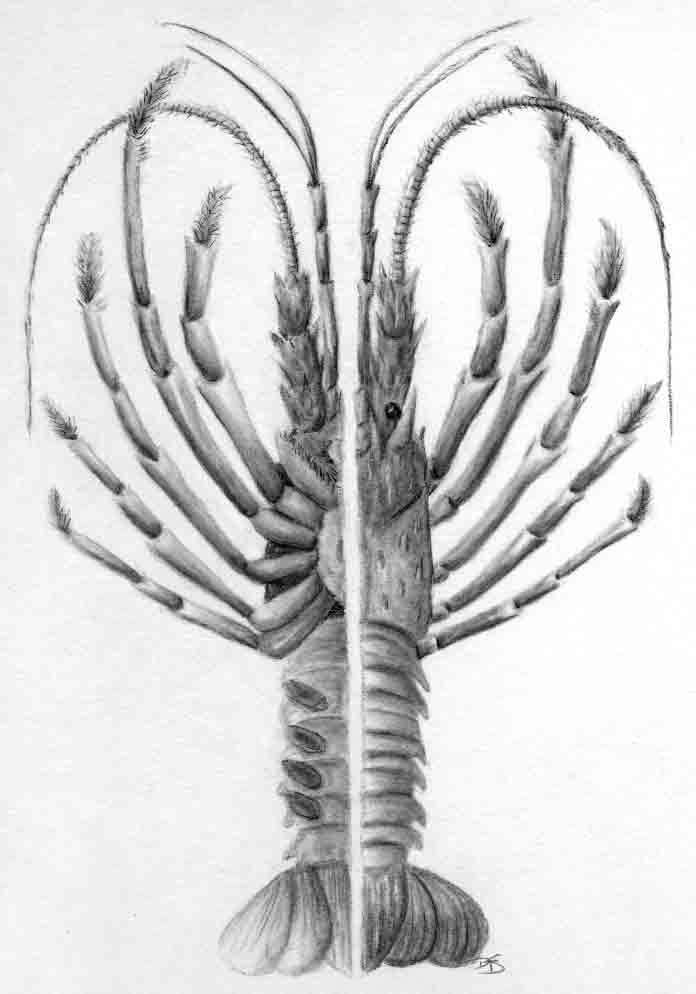

I wound up using an older illustration technique for this image. Carbon dust was introduced in 1911 by Max Brödel, the first director of the Department of Art as Applied to Medicine at Johns Hopkins University. It is one of those methods that produces amazing results, but has become lost due, I believe, to the complexity factor. Most illustration manuals devote two pages to setting up the supplies and preparing the board, followed by one paragraph on application, and another page on keeping everything clean. Computer illustration programs can now produce similar effects for publication with much less mess and without the storage issues carbon-dust involves.

Nonetheless, I readied my piles of dust scraped from various carbon pencils using fine sandpaper. I used good quality paint brushes that have never touched water, their bristles flecked with black dust. I measured the illustration board, lifted all blemishes from the surface with a kneaded eraser, and rubbed the whole thing with a chamois. Bilateral symmetry allowed me to render both the ventral and dorsal surfaces of the lobster in a compact illustration without losing detail.