Butterball Flew Coach

As part of Steinhart Aquarium's centennial, we’re featuring a different sea-lebrity on our blog every month. Follow @SteinhartBart on X for more archive deep-dives.

Before he became Steinhart Aquarium’s most famous resident for 17 years, Butterball the manatee was potentially someone’s dinner.

In September 1967, while visiting a fish market in Leticia, Colombia, a small city along the Amazon River bordering Peru and Brazil, Academy Trustee Wilson Meyer and Staff Biologist Maurice Rakowicz came across a juvenile Amazonian manatee (Trichechus inunguis) with a harpoon wound. The men negotiated a price for the ailing animal and bundled him into a coach seat on a commercial flight back to the States for emergency care, first at the Miami Seaquarium, then onto his final destination at Steinhart.

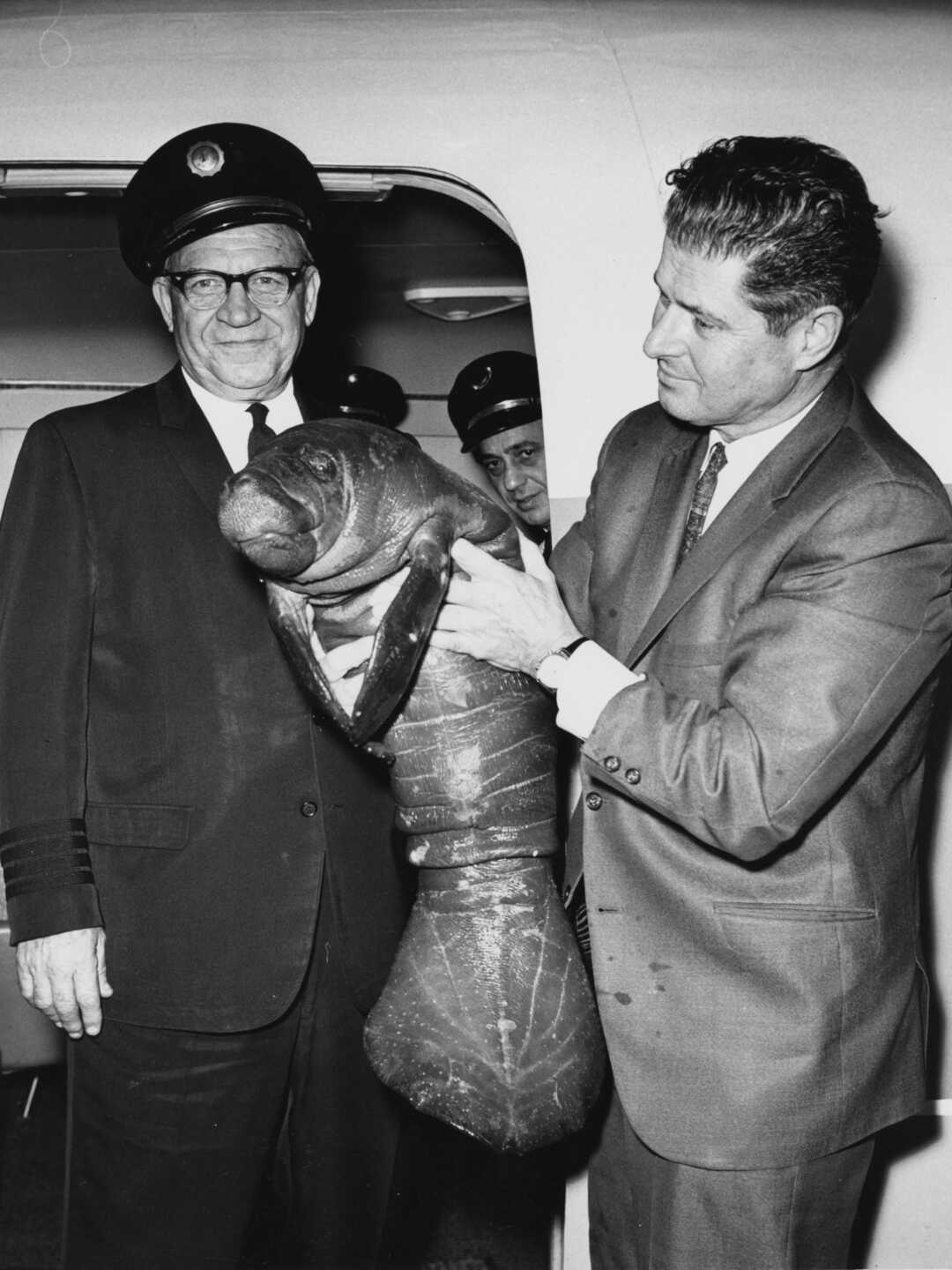

While we don’t have any testimonials from Butterball’s fellow passengers, we do have evidence of his arrival at San Francisco International Airport. In what must be one of the world's strangest photographs, former Steinhart Aquarium Superintendent and Curator Earl Herald holds the manatee confidently but nonchalantly as the National Airlines pilot looks at the camera. Butterball’s flippers touch demurely, the flashbulbs reflecting off his damp skin. The photographer remains unknown, but we're grateful they had a keen eye for the unusual.

Butterball's airlift certainly saved his life—but was he comfortable at cruising altitude? According to former Curator Tom Tucker, who, like Butterball, started his Academy career in 1967, “aquatic mammals do well out of water as long as their bodies are supported and their skin moisture is maintained.”

With his out-of-water odyssey finally over, Butterball began his star turn at Steinhart Aquarium. Recovering quickly from his harpoon injury thanks to expert care from Veterinarian Frederick Frye, Butterball’s celebrity status grew—and so did his stature. Arriving at 64 pounds, Butterball more than doubled in size by the end of his first year at the Academy, eventually reaching his maximum adult weight of 450 pounds.

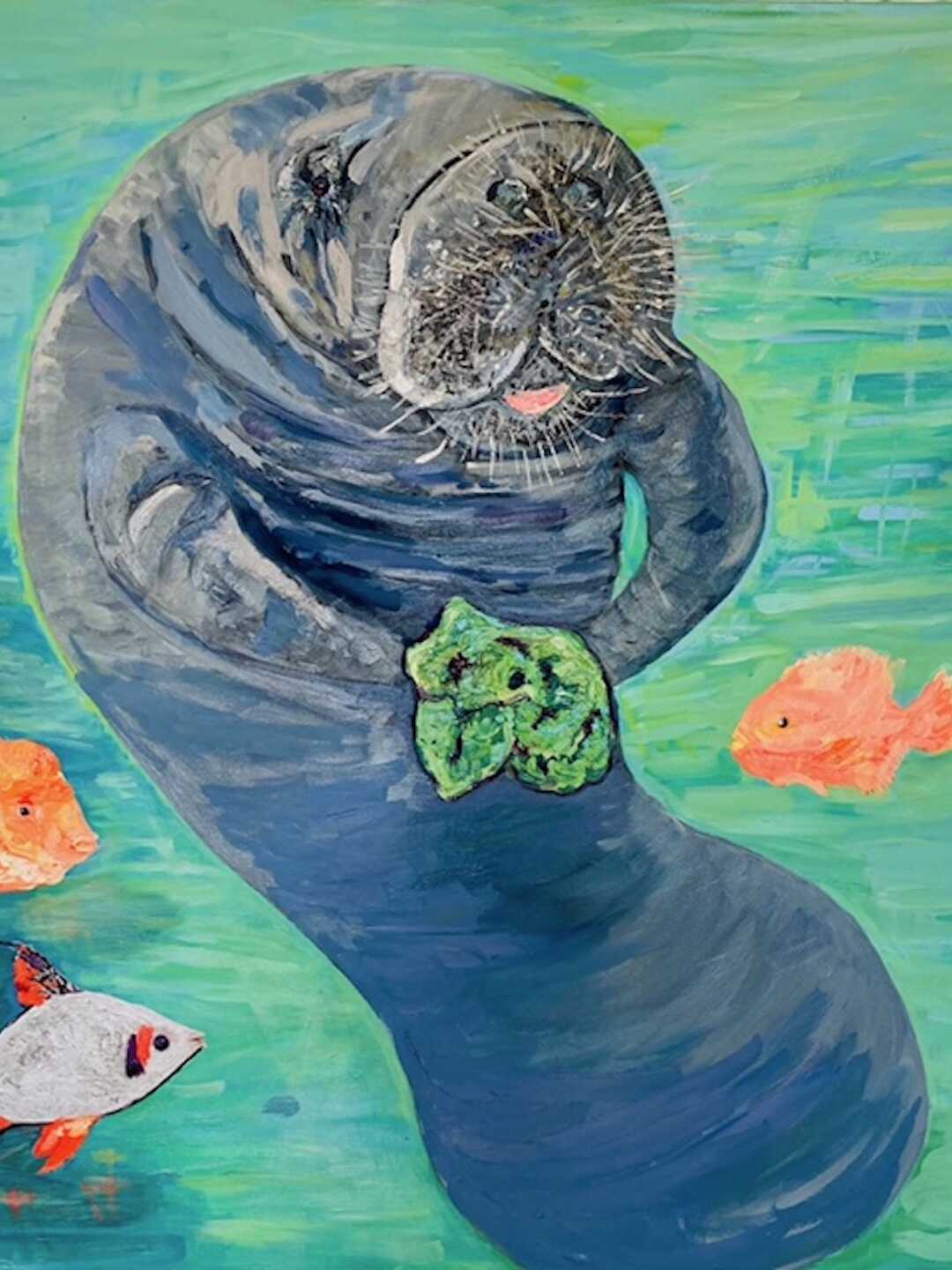

What do you feed a quarter-ton sea cow? For Butterball, about 25 heads of iceberg lettuce per day—the only food he'd accept for his first few years, much to the concern of his handlers. Luckily, his palate refined over time.

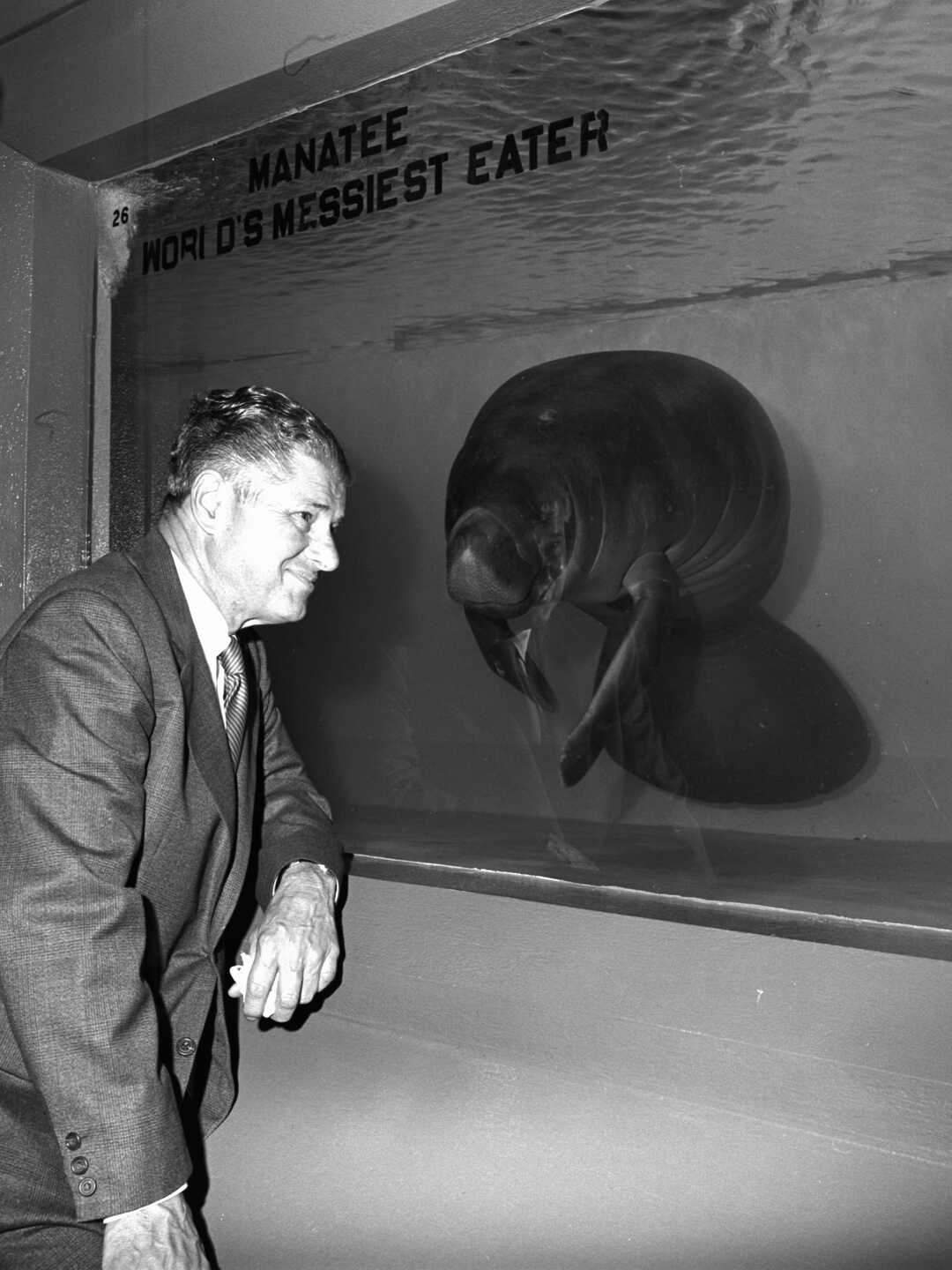

Due to his penchant for produce, Butterball was often surrounded by a swirl of leafy green flotsam, and a badge of honor was inscribed on his tank: “World’s Messiest Eater.”

There’s a reason manatees are also known as sea cows. Butterball had a bovine vibe: Large, unbothered, mindful in his approach to munching.

He did, however, have a streak of toxic masculinity.

“When female volunteers were scrubbing the glass inside his tank, he would grab their legs with his flippers,” recalls former Curator Tom Tucker.

It’s possible that Butterball was looking for love, but it’s also possible that he was just lonely. At one point, Tucker’s colleague Frank Glennon introduced another Amazon native, the Prochilodus fish, to Butterball’s habitat. The fish would graze on the algae covering Butterball's skin, providing relief for the manatee's itchiness—and perhaps a little companionship.

Tom Tucker, former Steinhart Aquarium curator

Butterball’s health began to decline in late-1980, and despite aggressive treatment, the beloved manatee died of a bacterial infection in September 1984.

In a paper published in a veterinary journal, Steinhart Pathologist Patricia Morales observed that at the end of his life, Butterball “became irritable and actively avoided brushing and diver contact, and no longer vocalized.” (Manatees do vocalize underwater, but how they actually produce their various chirps, grunts, and squeaks is still widely debated.)

Butterball's gentle demeanor and improbable origin story charmed millions of guests during his 17 years at Steinhart, and his death prompted an outpouring of grief from the public. With 10 academic research projects studying him over the course of his life, Butterball's legacy lives on through his contributions to manatee science.

Special thanks to former Steinhart Aquarium Director and Curator Emeritus John McCosker, PhD, Senior Director of Steinhart Aquarium Bart Shepherd, and former Steinhart Aquarium Curator Tom Tucker for their invaluable assistance researching this story. Their dedication to science, public education and engagement, and the wellbeing of the animals under their care is an inspiration to the Academy community and guests from around the world.