Although careful, meticulous observation is often underrated, Rich Mooi has built a career on his attention to detail. For more than 30 years, Mooi has been steadily filling in and building onto the phylogenetic tree of echinoderms, the enigmatic and rarely studied group of invertebrates that includes sea urchins, starfish, brittle stars, sand dollars, sea lilies, and sea cucumbers. The process of identifying important connections among various species of a phylum with a massive fossil record requires just this sort of painstaking observation, and Mooi is an expert at noticing similarities (and differences) down to the cellular level.

Mooi’s initial love of nature came from his parents, particularly his father, who had a lifelong interest in natural history. “They encouraged me to observe. My brother and I did a lot of nature walks with them and we’d walk trails and just notice stuff,” Mooi says. Like many kids of his generation, he was obsessed with the books and films of marine scientists like Rachel Carson and Jacques Cousteau. He remembers spending much of his time drawing: “I would sit down in a field of trilliums with a pile of paper and just draw them until I fell over,” he says. When he was 8, he created detailed “blueprints” for the research vessel he planned to use when he grew up and became a marine biologist. He pursued his interest in both art and science, producing lots of wildlife art, until it was time to decide what to study in college. He chose science, with the idea that it’d be easier to be a practicing scientist with art on the side than the other way around.

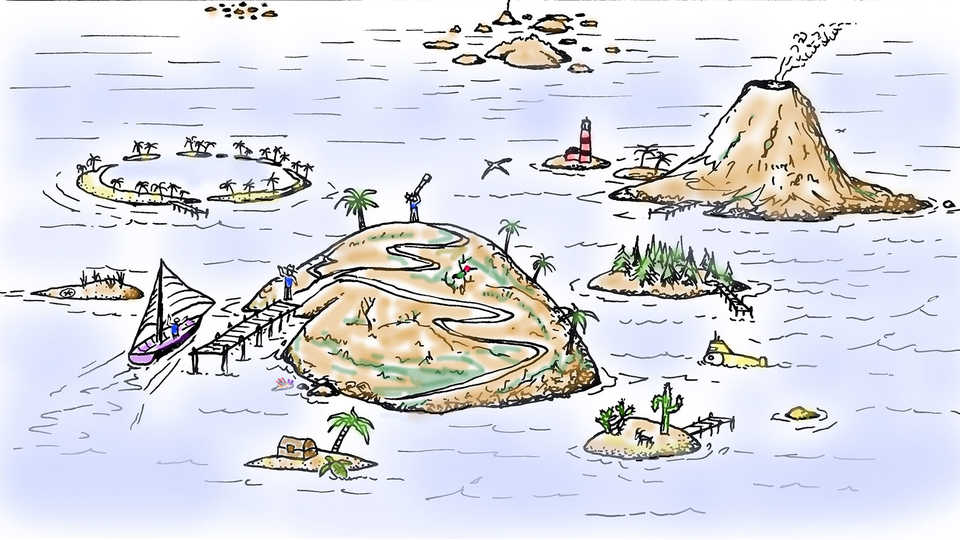

But he hasn’t really relegated art to the sidelines. “The intersection between art and science continues to be a very strong theme in my life,” says Mooi. Back when he was teaching invertebrate zoology, he made his students draw specimens with the belief that the active practice of reproducing features on paper would help them notice more than if they simply looked. Illustrations pop up in his work frequently, gracing the pages of scientific papers and educational videos, or as part of his work overseeing the Academy’s Biological Illustration Internship. The scientific illustrations that Mooi creates to accompany his research provide clarity for concepts difficult to understand even outside the context of a scientific paper. “Because you can edit out the extraneous ambiguous features, a simple drawing produces a more powerful message,” says Mooi. “A picture truly is worth a thousand words, and I think that’s a serious underestimate.”