Scientist Spotlight

Bart Shepherd

As Senior Director of Steinhart Aquarium, Bart Shepherd oversees the Academy’s nearly 60,000 live plants and animals. With more than 1,000 species on display throughout the Academy, the Steinhart is home to one of the most biologically diverse aquarium collections in the world.

Follow Bart on Twitter at @SteinhartBart.

Childhood dream

Although he grew up on the other side of the country in Virginia’s Chesapeake Bay, Bart Shepherd was drawn to the Academy at an early age. A youthful aquarium hobbyist who began keeping tropical fish at the age of six, he remembers how his reference books and magazines were filled with photos of colorful and unusual species taken at Steinhart Aquarium. Visiting as a tourist in 1994, Shepherd was excited to learn of the Steinhart’s many milestones.

“Under John McCosker’s leadership in the seventies and eighties, we were the first to display white sharks and flashlight fish,” he says. “Before that, Earl Herald put Steinhart on the map with the country’s first televised science program, Science in Action. These guys were charismatic spokesmen and strong leaders.”

This early inspiration combined with the cold winters at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York, compelled Shepherd to move west. With every intention of finishing his graduate thesis, he packed up his Volkswagen Jetta and drove to San Francisco in August 1996.

“Within a few months,” he admits, “I needed a break from staring at the computer monitor. So I got the name of Steinhart’s then-curator, Tom Tucker, from a former colleague at the Virginia Aquarium. I interviewed with him to be a volunteer, and we really hit it off.”

Soon, Shepherd was spending his afternoons feeding fish and cleaning the Aquarium’s roundabout and stingray holding pool. A few months later in February 1997, he was offered a full-time job. In 2011, after fourteen years at the Academy as Aquatic Biologist, Senior Aquatic Biologist and Curator, Shepherd was named Director of Steinhart Aquarium.

“I’m a scientist. Ultimately, I don’t believe in destiny,” he says. “But when I think back on moving out here without knowing a single person at the Academy, I have to say there was something very special about this journey.

Diving

SCUBA diving has played a central role in Bart Shepherd’s career.

“I’ve always been fascinated with what lies beneath,” says the Director of Steinhart Aquarium. “It’s not for everyone—there is always some risk involved. But it offers you access to one of the most amazing parts of the planet. And you feel weightless, like you’re flying.”

That’s Shepherd’s heartfelt assessment after completing more than 250 dives. But his experience earning a basic open-water diving certificate as a college freshman in 1989 almost torpedoed his enthusiasm.

“We performed our open-water dives in early spring in a freezing cold reservoir in Hampton, Virginia,” he says, recalling the P.E. class offered at the College of William and Mary. “The water was so murky; visibility was less than twelve inches.” There weren’t enough wetsuits for the class, so Shepherd suited up in his classmate’s cold and dripping wet neoprene. During one skill test, in which the instructor had the students drop to the reservoir’s bottom and remove their masks, “A fish swam out of nowhere, looked me in the eye, and then disappeared,” Shepherd says with a shudder. “It nearly scared me to death.”

Luckily, Shepherd could draw upon pleasant memories of snorkeling in the Caribbean with his family during summer vacations. “You couldn’t get me out of the water,” he laughs. “My back would get sunburned until I learned to wear a shirt.” He returned to warmer waters to earn his advanced open-water certificate, performing field dives in Crystal River, Florida in 1991. Highlights included a dive to 100 feet, underwater navigation, search-and-rescue maneuvers and his first night dive in water that was warm, clear, and filled with fish.

But it was a diving experience in 1994 that proved transformative. That year, having just left the Virginia Aquarium, Shepherd participated in a two-week Earthwatch program on Maui organized by the Pacific Whale Foundation. The group of students and volunteers surveyed the health of the Hawaiian Islands’ threatened reefs. They assessed fish populations and monitored coral diversity and distribution, collecting data for a long-term reef-monitoring project. Through it all, Shepherd held his own with the graduate students and project assistants, visually identifying the corals and matching fish to their scientific names.

“I’d never seen any of this stuff in the wild,” he says. “I knew it from books and magazines and aquariums. This really boosted my confidence. It showed me that I could do this and, more importantly, that I loved it.”

Based on his experience, Shepherd decided to return to school and pursue a Master’s degree in biology at Vassar College. “Coral reef science is very competitive,” he says. “The best programs have only a small number of spots. My strategy was to find a way to work on coral reef biology through opportunities within the world of public aquariums.”

His strategy worked. Hired by the Academy upon completion of his M.S. degree in 1997, Shepherd rose through the ranks from volunteer to Aquatic Biologist to Curator. He was named Director of Steinhart Aquarium in 2011.

Twilight zone

Every year, Academy scientists conduct some 500 SCUBA dives around the world, in addition to the more than 2,000 aquarium dives conducted annually.

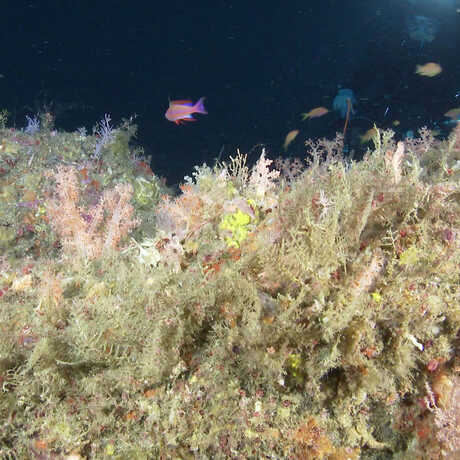

Since 2006, Shepherd has traveled to the Philippines to explore coral reefs, diving to depths of up to 130 feet. It was on one such expedition in the Verde Island Passage that Shepherd saw a giant stingray.

“It was the largest one I’ve ever seen,” he says. “The opportunity for new discoveries at these depths is tremendous.”

For this reason, Shepherd is excited about a new Academy-based initiative to explore ocean life at even greater depths—between 100 and 500 feet—in a region known as “the twilight zone.” Located below the levels explored with recreational diving equipment and above the depths typically reached by submersibles, it’s a habitat that sees very little light and one that’s ripe for discovery.

Luiz Rocha, Curator of the Academy’s Ichthyology Department, first advocated the idea of exploring life at these depths and found enthusiastic support from Shepherd and Elliott Jessup, Academy Diving Safety Officer. But it wouldn’t be easy. Such dives are made possible through special technology known as closed-circuit rebreather diving. This includes multiple tanks of custom gas blends, a carbon dioxide scrubber, and electronic monitoring equipment. The dive team uses diver propulsion vehicles, often called scooters, to quickly descend to deep reefs.

“Without those scooters, you couldn’t do these dives,” Shepherd laughs. “You just can’t swim with all that equipment.”

Shepherd has earned mixed-gas, closed-circuit rebreather, and extreme exposure certifications. These allow him to dive down to 500 feet using tri-mix: a blend of helium, oxygen and nitrogen. So far, he’s completed more than 40 dives on the rebreather—to depths of more than 350 feet.

“The technology pushes the envelope on what’s possible,” says Shepherd. He notes that any expeditions to the twilight zone will be expensive and time-consuming.

“It’s a lot like flying an airplane,” he says, “You don’t just train for an afternoon and then go out in the field. There’s a lot of technology involved. You must be in good physical shape and pay complete attention at all times.”

Is it worth it?

“Absolutely,” he exclaims. “The transition from shallow-water coral reef habitat to a deeper habitat is dramatic.”

At 100 to 120 feet, Shepherd says, the edge of the reef appears to be teased apart.

“The shallow-water, sunlight-loving corals start to transition to a mucky, sandy-bottom habitat,” he says. “But there’s a whole new, largely unexplored community of creatures living there. The soft corals that emerge from the sand look grey at first. But when you shine a light on them, they are revealed to be a Technicolor garden, just a dazzling array of brilliant oranges, reds and purples."

Shepherd is excited to leverage the expertise of his diving staff to aid the research of Academy scientists.

“This initiative is about exploration. But then, we’ll also bring back rarely seen species and exhibit them on the public floor.”

Husbandry challenges

As partners in the Association of Zoos and Aquariums’ Species Survival Plan Program, Academy biologists work with other institutions to breed and raise thirty species in collaboratively managed programs.

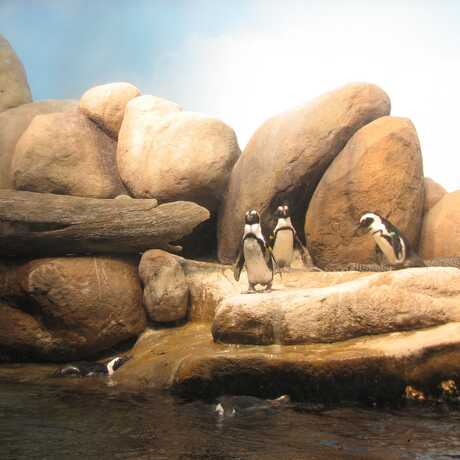

Among the species bred in-house are the African penguin (Spheniscus demersus), pot-bellied seahorse (Hippocampus abdominalis), Jackson’s chameleon (Trioceros jacksonii), golden mantella (Mantella aurantiaca), dwarf cuttlefish (Sepia bandensis), several species of freshwater fishes from Madagascar, neotropical passerine songbirds, and numerous species of jellyfish.

According to Shepherd, in the aquarium industry, more than 90 percent of the freshwater fish in the world’s aquariums are captive-bred, with less than 10 percent of such fish collected in the wild. But those numbers are reversed for the marine fishes displayed in saltwater tanks.

The key difference is that marine fish have a very long larval stage, during which tiny larvae feed on even smaller food sources within the ocean’s plankton.

“To successfully breed marine fish,” Shepherd says, “you need to feed these fishes through a whole range of sizes. It can take many weeks to get past the larval stage. They aren’t large enough to eat more easily prepared diets until they’re juvenile fish. Finding and culturing large amounts of the right food sources for growing fish larvae remains a challenge for aquaria.”

Sustaining coral reefs

Steinhart Aquarium first opened its doors to the public on September 29, 1923. The Aquarium has accomplished a lot since then, but Bart Shepherd still wants to break down barriers.

His first goal is to increase the opportunities for collaboration between the people in the Academy doing academic research and those focused on animal husbandry. “We’re all Academy scientists,” Shepherd says. “Let’s find more ways to work together to accomplish the Academy’s mission, to explore, explain, and sustain life.”

Secondly, Shepherd says the Aquarium staff has long sought opportunities to do more field-based conservation. While stressing the importance of the Academy’s in-house breeding program and the excitement of building new exhibits, Shepherd also states, “We want to do more than discuss the plight of these animals in the wild. We want to help improve the conditions for species in the natural world.”

To that end, Shepherd is expanding the Academy’s ongoing partnership with the SECORE Foundation, with the goal of introducing the techniques pioneered by this group to the Philippines.

For context, Shepherd pulls up a grim series of numbers: The survival of 75 percent of the world’s tropical coral reefs is threatened and at least 25 percent of Earth’s reefs have already been lost. SECORE, a nonprofit foundation headquartered in Germany, with scientific partners drawn from the world’s foremost aquariums, universities and conservation organizations, has pioneered techniques that enable the cultivation of coral in the wild.

The SECORE approach uses special nets to collect sperm and egg bundles during spawning events in the wild, which occur predictably in the days surrounding the full moon.

“When coral spawns, it’s like snow in reverse,” Shepherd says with an air of wonder. “The sperm and egg bundles are buoyant, drifting upwards. Fertilization and development take place right on the surface of the water.”

Using SECORE’s approach, the Academy's team fertilizes the eggs in the lab, cultures the larvae for a few days, and then settles them onto specialized tiles that can be planted back out on the reef.

Collecting these gametes for cultivation and returning juvenile corals to the wild can help damaged reefs recover and give them a better chance of surviving long into the future.

Until now, the Foundation has focused its efforts in the Caribbean. “The Academy is going to help SECORE expand globally,” says Shepherd. “We’re going to help introduce their skills and technology into the Philippines.” Doing so, Shepherd hopes, will help the Academy further its mission to sustain this and other important reef ecosystems for generations to come.

Department: Steinhart Aquarium

Title: Senior Director, Steinhart Aquarium

Expeditions: 11

Number of Dives: 250+

Certifications: Open-Water diving, Advanced Open Water diving, Nitrox diving, diver propulsion vehicle use, Prism2 air diluent, closed-circuit rebreather diving

Videos:

Steinhart Aquarium, Then and Now

Philippine Coral Reef Exhibit

Collecting Corals

Preserving Our Shared Resource

Giant Stingray in the Philippines

Chat with an Academy Scientist

Related Website:

SECORE

Select Publications:

Click to view

Be mesmerized by colorful coral reef fish, soaring stingrays, and adorable African penguins—streaming live to your device, 24/7.