We're open daily! View holiday hours

Science News

Within Curiosity's Reach

December 10, 2013

by Molly Michelson

The surface of Mars is currently not very friendly to life. The harsh conditions include wind erosion and radiation from cosmic rays. In the midst of this, the Curiosity rover is digging into Mars’s past, looking for signs of life.

Yesterday at a press conference at the American Geophysical Union Meeting in San Francisco, five scientists with the Curiosity science team presented the latest findings from this seemingly impossible mission.

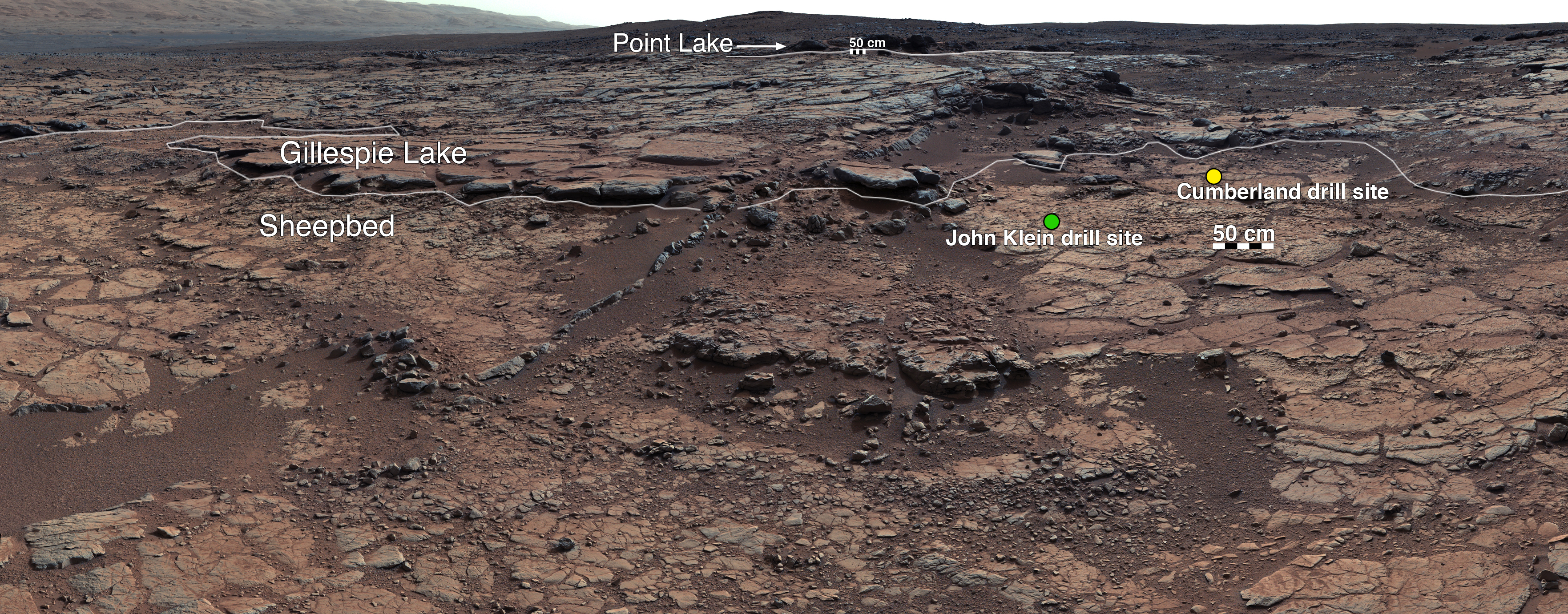

Last spring, the team announced that Curiosity detected a past lake environment at the John Klein drilling site. And not just a habitable lake environment, but also a system of streams and groundwater at the site as the surface water dried up. And as John Grotzinger of Caltech mentioned at the press conference, these habitable systems likely existed for several million years.

Now that a past habitable environment has been confirmed, at the conference Grotzinger said the mission is “turning a corner—from detecting habitability, to detecting organics.” (Helpful hint from a press release: “Organic chemicals are building blocks of life, although they also can be produced without any biology.”) And he stressed that while this new part of the mission is difficult to carry out, they are quickly learning new ways to discover these organics.

Much of this learning comes from the chemistry discovered on the surface and from the drilling Curiosity has done at John Klein and another site, Cumberland. Jennifer Eigenbrode of NASA Goddard said that the SAM instrument (Sample Analysis at Mars) measured carbon and nitrogen, both signs of life, through combustion experiments, but they can’t tell whether these chemicals are organic or mineral.

Organics at the surface are exposed to cosmic ray irradiation and are destroyed. So the trick is to drill down to find them. At the surface of the current site, due to its age—about 80 million years, according to measurements announced at the press conference—if organics are present, they would exist at three meters or lower beneath the surface. But Curiosity is only able to drill about five centimeters down.

This new surface age measurement plays a key role in understanding how long this soil has been exposed to the harsh Martian conditions. If the team can find a site less hit by radiation—somehow protected from the cosmic rays and wind erosion—perhaps the organic chemicals will reside at a shallower depth, where Curiosity can reach them.

So two months from now, the team hopes that Curiosity will reach the KMS-9 outcrop—about halfway to its final destination at Mount Sharp. According to images from Mars HIRISE, the site is at the edge of an escarpment where the rock has retreated more recently, reducing the chance of long-term radiation. Perhaps organics are only a few centimeters down at this site, and thus within Curiosity’s reach.

In addition to the press conference, six papers on the latest findings were published yesterday in Science Express.

Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS