Science News

Whale Echolocation Origins

March 12, 2014

by Molly Michelson

Toothed whales, like their mammalian relatives bats, use echolocation to navigate and hunt prey in the dark—in this case, the deep and murky ocean. But the evolution and origin of echolocation in these marine mammals has remained somewhat of a mystery. Now a 28 million-year-old toothed whale fossil is helping shed new light on that mystery.

Sperm whales, dolphins, porpoises, orcas and other toothed whales make click-like sounds as an echolocation call. They send their calls through their melon—an organ in their forehead made up of fatty tissue—and out of their body through “phonic lips” within their nasal passages, beneath the blowhole. According to the University of Cambridge’s Map of Life, the melon

acts as an acoustic lens and emits a focused beam of sound. The echoes are primarily received through the lower jaw, which is surrounded by complex fatty structures, and conveyed to the ear through a continuous fat-filled canal.

Toothed whales also have an asymmetrical head, thought to be involved in echolocation as well.

(You can find great visualizations of CT and MRI scans of whales’ heads at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution website, in case you’re curious.)

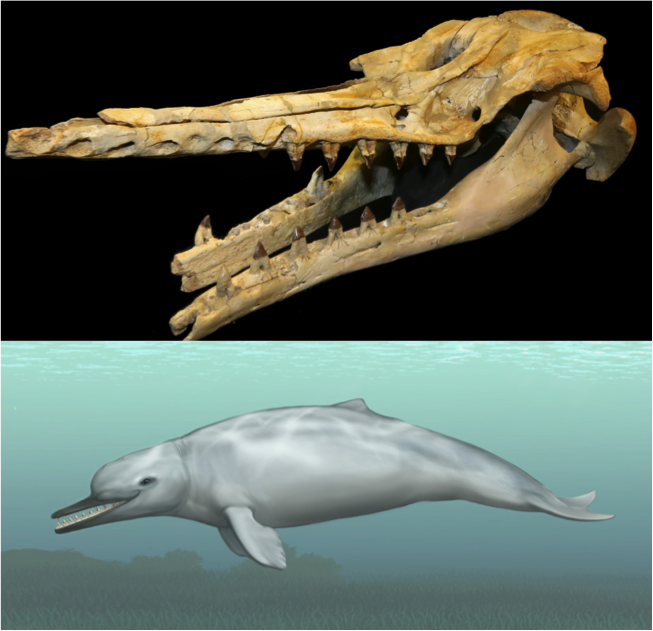

In other words, the whales’ anatomy says a lot about the echolocation function. So when researchers came across a toothed whale fossil in North Carolina, they carefully observed the skull for signs of its sonar abilities.

The team describes the 28 million-year-old fossil as a new species, Cotylocara macei, today in the journal Nature. They report that the animal’s skull has several features suggestive of a rudimentary form of echolocation, including cranial asymmetry and a dense upper jaw. In addition, while fossils of the soft tissue are not present, the team believes “that some aspects of these tissues can be inferred from” basins within the skull.

The analysis suggests that echolocation emerged very early in the history of toothed whales, soon after their divergence from the ancestors of baleen whales. “The most important conclusion of our study involves the evolution of echolocation and the complex anatomy that underlies this behavior,” says lead author Jonathan Geisler of the New York Institute of Technology. “This was occurring at the same time that whales were diversifying in terms of feeding behavior, body size, and relative brain size.”

Now that’s using your melon!

Images: Skull, James Carew and Mitchell Colgan; Artistic Reconstruction, Carl Buell