Each month, renowned astronomers share their latest research at Morrison Planetarium.

Universe Update

The End (or Beginning?) of the Kepler Era

The Kepler spacecraft launched in 2009 with the mission to determine whether we are alone in this vast Universe, and if we’re not alone, just how common Earth-like planets are in the galaxy.

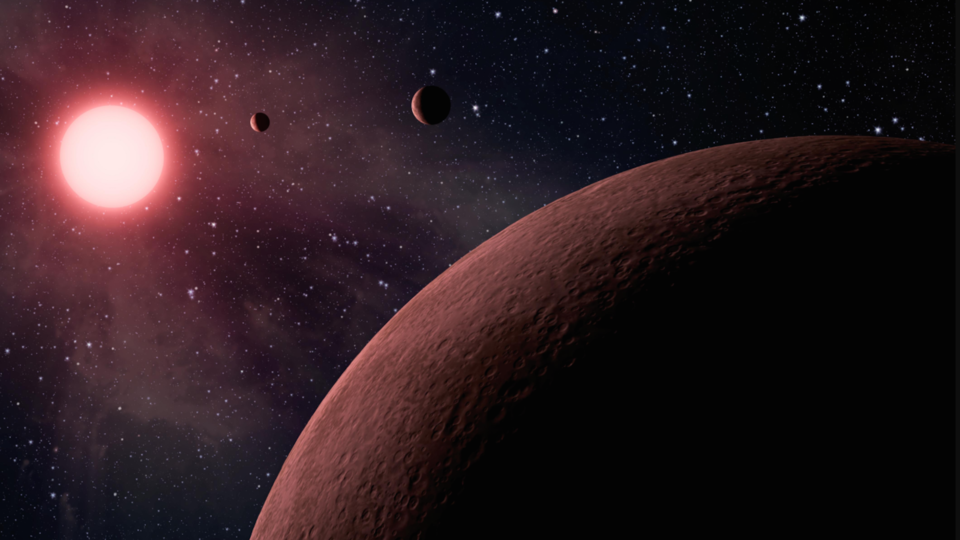

Today, NASA scientists held a press conference to release the final data of the Kepler survey. The announcement coincides with a week-long meeting on exoplanets at NASA Ames Research Center here in northern California. The new results include 219 additional exoplanet candidates with ten inside their parent stars’ respective habitable zones. Since the mission began, Kepler has found more than 2,300 confirmed exoplanets, of which 49 (including the ten announced today) are terrestrial, close to Earth-sized, and within their habitable zones.

Within those new ten, said Susan Thompson, Kepler research scientist for the SETI Institute and lead author of the catalog study, KOI 7711 is the most promising of the bunch. At 1.3 times Earth’s diameter, it’s the closest to Earth in terms of size—and it’s also a similar distance from its sun-like star, which means it gets the same amount of heat from its star as we get from ours, she explained. “But we’re not sure about the rest. Is there water? An atmosphere? Remember, if you look at our system, Venus and Mars are also in the habitable zone, and I sure don’t want to live on either of those planets.”

In addition to the newly discovered planets, Caltech scientist B.J. Fulton announced a distinction between the most commonly found small planets. Using the W. M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii, Fulton and colleagues were able to look much closer—with about four times more precision than Kepler had observed—at the size of 2,000 small exoplanets. “Before, sorting the planets by size was like trying to sort grains of sand with your naked eye,” Fulton said. “Getting the spectra from Keck is like going out and grabbing a magnifying glass. We could see details that we couldn’t before.”

Those details reveal that our galaxy has a strong preference for two types of planets: rocky planets up to 1.75 times the size of Earth (we call the biggest ones “super-Earths”), and gas-enshrouded worlds 2 to 3.5 times the size of Earth (“mini-Neptunes”). The researchers believe this has to do with the balance of hydrogen and helium on the planet. Too much hydrogen could tilt a planet to become more of a mini-Neptune than a super-Earth, Fulton explained. There are very few planets between the two in the entire Kepler survey. “These results sharpen the dividing line between habitable and not-habitable,” he said, making it easier for future missions to look for life.

Speaking of future missions, when the panel of scientists were asked if they were sad about the end of Kepler survey results, Thompson and Courtney Dressing, NASA Sagan Fellow at Caltech, explained that Kepler results are only the beginning! Scientists are now excited to refine and expand these results with K2 and the upcoming Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) and James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

K2 is the extension of the Kepler mission, looking beyond the Cygnus constellation allowing us to see exoplanets of different ages, metal content, and more low-density planets, Dressing said. It may allow us to understand if the population we see in the Kepler survey is what we will see everywhere.

TESS, which launches next spring, will survey even more of the sky to answer that question, and JWST, launching in the fall of 2018, will allow us to measure these planets’ atmospheres, getting us even closer to answering the question Kepler started with: How common are Earth-like planets? Are we alone?

(As part of the week-long Kepler science conference taking place in the Bay Area, Morrison Planetarium will be hosting two rock-star scientists as part of our monthly Benjamin Dean Astronomy Lecture Series tonight, Monday, June 19. Both researchers do cutting edge work with Kepler: Dave Charbonneau will talk about exoplanets, while Ruth Angus will describe her work teasing out the ages of stars. Join us at Morrison Planetarium Monday evening to help us celebrate Kepler Exoplanet Week!)