Science News

Rivers in Trouble

October 5, 2010

Last week, scientists of varying disciplines from across the globe described a startlingly dire portrait of the world’s rivers.

Published in the journal Nature, the study reveals that nearly 80 percent of the world's human population lives in areas where river waters are highly threatened—posing a major threat to human water security. In addition, the poor health of these rivers is pushing thousands of species of plants and animals to the risk of extinction.

"Rivers around the world really are in a crisis state," says Peter B. McIntyre, a senior author of the new study and a professor of zoology at the University of Wisconsin.

Examining the influence of numerous types of threats to water quality and aquatic life across all of the world's river systems, the study is the first to explicitly assess both human water security and biodiversity in parallel. Fresh water is widely regarded as the world's most essential natural resource, underpinning human life and economic development as well as the existence of countless organisms ranging from microscopic life to fish, amphibians, birds and terrestrial animals of all kinds.

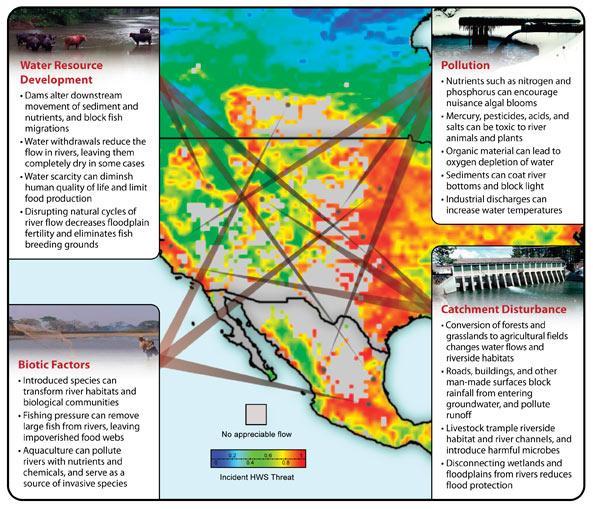

What jumps out, say the authors, is that rivers in different parts of the world are subject to similar types of stresses, such things as damming, agricultural intensification, industrial development, introduction of non-native species and other factors. In addition, rivers in developed nations are just as damaged as those in developing parts of the world.

The analysis used data sets on river stressors around the world. Built into state-of-the-art computer models, the data yield maps that integrate all of the individual stressors into aggregate indices of threat. The same strategy and data, the researchers hope, can be used by governments worldwide to assess river health and improve approaches to protecting human and biodiversity interests.

“We've created a systematic framework to look at the human water security and biodiversity domains on an equal footing,” author Charles J. Vörösmarty of the City University of New York says. “We can now begin presenting different options to decision makers to create environmental blueprints for the future.”

This new tool provides another means by which we can all work to protect these precious resources before the well runs dry.

Illustration by Barry Carlsen