Universe Update

Observations: Observing for minutes or hours

Every other week, we take a peek at some of the discoveries made at the telescopes that dot the Chilean landscape. Why Chile? Well, not only are these observatories making some of the most groundbreaking findings in the cosmos, but it’s also a great way to promote our new planetarium show, Big Astronomy: People, Places, Discoveries, which currently broadcasts live online every Wednesday at 11:30 a.m. (Tomorrow’s broadcast on YouTube 360° will take place here.)

Chile’s geography and climate make it the perfect place for observational astronomy, and it’s an international effort with partnerships from governments around the world running these sites. That’s right, governments! These telescopes are largely a public-funded endeavor, and that means that the discoveries they make belong to all of us.

Today, we’ll travel to the Atacama desert, one of the driest places on our planet (and one of the most beautiful, too), to two different telescopes, pointed at two very different spots in the Universe—one right in our solar system, the other when the Universe was only a couple billion years old. Astronomers plan for months or years for their time on these telescopes, with discoveries sometimes taking dozens of hours, or in the first discovery below, 30 minutes! The findings can confirm suspicions and garner new surprises, all of it adding to our collective knowledge and human understanding of the Universe.

Such as… How fast are the winds on Jupiter? According to a new study, it took the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) only 30 minutes to observe incredibly powerful winds in the gas giant’s stratosphere, with speeds of up to 1,450 kilometers an hour near Jupiter’s poles. (They’re only about 600 kilometers an hour near the equator.) “The high levels of detail we achieved in this short time really demonstrate the power of the ALMA observations,” says Thomas Greathouse, a scientist at the Southwest Research Institute and co-author of the study. “It is astounding to me to see the first direct measurement of these winds.” (We were well versed in the speed of winds above the stratosphere, but this is the first measurement of these winds deeper in the jovian atmosphere.)

The team used 42 of ALMA’s 66 high-precision antennas to analyze the hydrogen cyanide molecules that have been moving around in Jupiter’s stratosphere since the impact of comet Shoemaker–Levy 9 in 1994. The ALMA data allowed the researchers to measure the Doppler shift—tiny changes in the frequency of the radiation emitted by the molecules—caused by the winds in this region of the planet. Maybe soemday we’ll be getting jovian weather reports from ALMA?

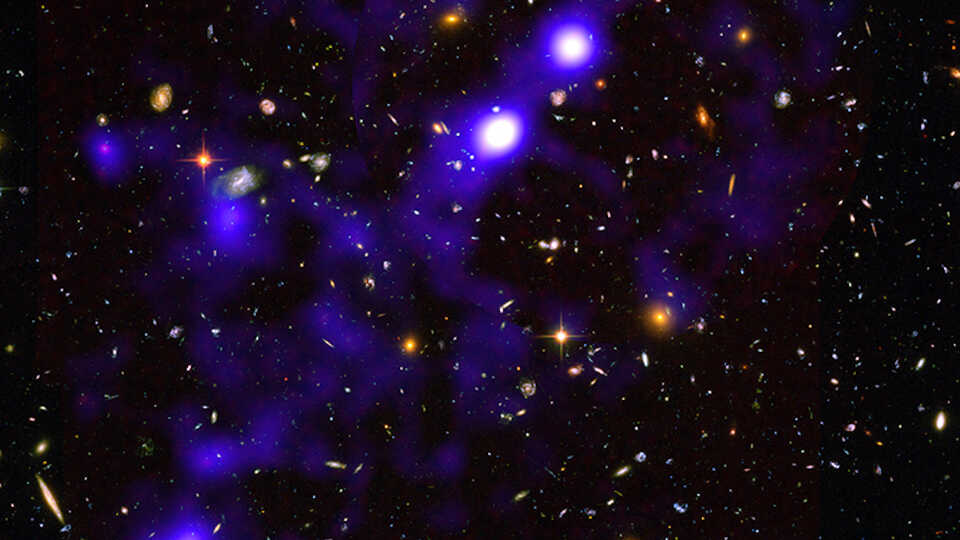

And much. Much farther from home… Astronomers believe that galaxies are born in filaments of gas. But while these filaments were predicted by cosmological models, they had never before been observed. Until now. A team of researchers, using the Multi-Unit Spectroscopic Explorer (MUSE) instrument installed on the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in northern Chile, pointed the telescope to a region in the early Universe, just 1 to 2 billion years after the Big Bang, for over 140 hours! For the first time, they witnessed light from the hydrogen filaments as seen in the second image above. Additional simulations suggest the light came from an unknown population of billions of dwarf galaxies spawning a host of stars. Although these galaxies are too faint to be detected individually with current instruments, their existence will have major consequences for galaxy formation models, with implications that scientists are only just beginning to explore. Their study was published last week in Astronomy & Astrophysics.

From nearby to far away, using observations that could occur over a lunch break or could take nearly a week, astronomers continue to make astounding discoveries using Chile’s great observatories.