Science News

New Galápagos Bird—Now Gone

Many Wednesdays we post our New Discoveries stories—a partnership with Stanford that reveals new species recently found and published, demonstrating how much we still have to learn about life on Earth. While today’s tale could fit under these new discoveries, sadly, this is a brand-new species that is now extinct.

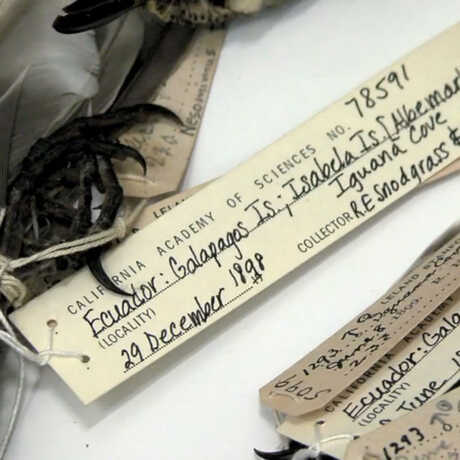

The vermilion flycatcher (Pyrocephalus rubinus) is a wide-ranging bird found across the Americas and the Galápagos Islands with 12 recognized subspecies. The Academy’s Jack Dumbacher and his colleagues recently used molecular data from samples of museum specimens up to 100 years old to tease apart the complex evolutionary history of these birds. “Access to museum collections such as the Academy’s for pursuing these types of studies is invaluable,” says Christopher Witt, of the University of New Mexico. “Preserved specimens can provide the crucial links needed to better understand how life on Earth evolved.”

In the process, two subspecies of the vermilion flycatcher, both found only in the Galápagos, were determined to be so genetically distinct that the team elevated them to full species status: Pyrocephalus nanus (throughout most of the Galápagos) and Pyrocephalus dubius (only on the island of San Cristóbal). The latter—significantly smaller and subtly different in color from the other species—is commonly known as the San Cristóbal vermilion flycatcher and hasn’t been seen since 1987.

“A species of bird that may be extinct in the Galápagos is a big deal,” says Dumbacher, Academy curator of ornithology and mammalogy. “This marks an important landmark for conservation in the Galápagos, and a call to arms to understand why these birds have declined.”

What exactly drove the San Cristóbal vermilion flycatcher to extinction remains unknown, but two invasive threats to the archipelago likely played a part: rats and parasitic flies (Philornis downsi). Rats often climb into nests to eat bird eggs, while the parasitic fly can kill growing chicks. These invasive species are severely impacting the remaining populations of other vermilion flycatchers in the Galápagos, with some islands no longer hosting populations that once thrived there.

“Sadly, we appear to have lost the San Cristóbal vermilion flycatcher,” says Dumbacher, “but we hope that one positive outcome of this research is that we can redouble our efforts to understand its decline and highlight the plight of the remaining species before they follow the same fate.”

Dumbacher, Witt and their colleagues published their findings in Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution last spring, and the scientists are on-hand at the North American Ornithological Conference this week to discuss the plight of these birds and their relatives.

Images: Alvaro Jaramillo and Jack Dumbacher