Science News

Global Response to Human Gene Editing

Over the last several months, there’s been a lot in the news about human gene editing—the ability to edit a snippet of our DNA to help protect us from disease and more. Not surprisingly, a new tool called CRISPR-Cas is garnering a huge reaction—both positive and negative. In fact, an entire session at the recent American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) Annual Meeting was devoted not to the technology, but rather, the global response to it, and the regulations (or lack thereof) surrounding gene editing.

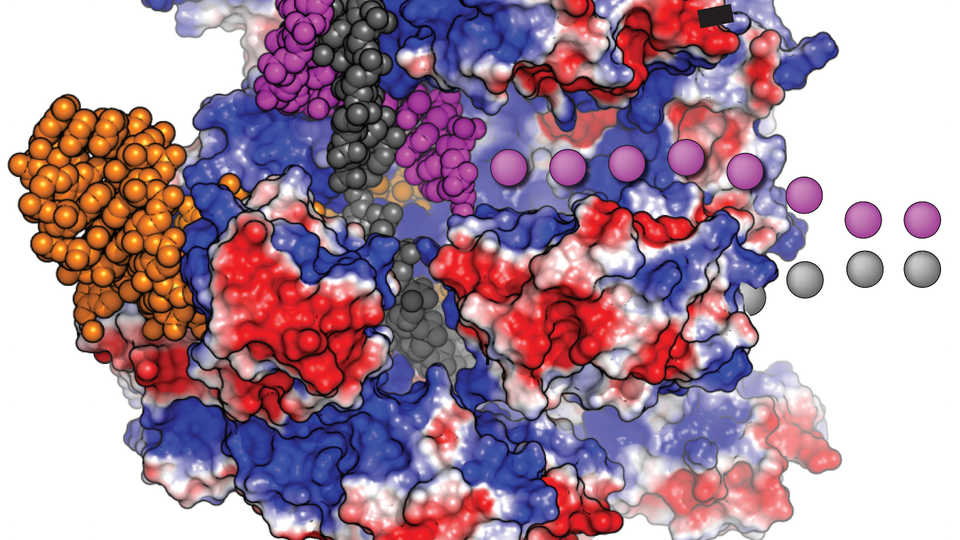

So what the heck is it? We asked Daniel Greenburg, one of the super smart iGEM Stanford-Brown team members who was at the Academy last fall. “CRISPR-Cas is a really specific type of molecular scissor,” he told us. “So if you want to try to knock out a certain kind of gene, you can design this special kind of RNA that targets the gene that you want to cut.” The iGEM team only uses CRISPR-Cas for altering bacteria, but the tool can be used in any living thing, including humans, amphipods, and headline-grabbing pigs. It’s so revolutionary that the technology was named the 2015 “Breakthrough of the Year” by Science magazine.

While the session was mostly devoted to the ethics of the new technology, many questions surfaced surrounding its invention. That’s because a huge debate has erupted about the patent for CRISPR-Cas. Two UC Berkeley female scientists developed the tool at the same time as researchers from the Broad Institute. KQED covers the patent war very well and speaker Robin Lovell-Badge avoided the subject by telling the crowd at the conference that bacteria invented gene editing.

But the session was truly meant to judge the reactions of the International Summit on Human Gene Editing that occurred last December. Held in Washington, D.C., the meeting included the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the Royal Society, the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, and the U.S. National Academy of Medicine. According to the National Academies website, “...the summit convened experts from around the world to discuss the scientific, ethical, and governance issues associated with human gene-editing research.” Even one of the CRISPR-Cas UC Berkeley inventors weighed in.

First the summit determined that, “Basic and preclinical research is clearly needed and should proceed, subject to appropriate legal and ethical rules and oversight…” And clinical somatic use could proceed, such as helping HIV patients or others with diseases that CRISPR-Cas might be able to eliminate, “because proposed clinical uses are intended to affect only the individual who receives them and they can weigh the risks and potential benefits,” Lovell-Badge said. Human gene editing isn’t without side effects.

But the summit was much more cautious about germline use. This is the gene editing of embryos, that brings the fear of things like designer genes and Gattaca. According to Lovell-Badge, this provision states that it is irresponsible to proceed with germline until safety and efficacy issues have been resolved. The thought is to do your research, try somatic cells first, and then move forward.

Finally, the summit determined that there should be an ongoing forum to continue the conversation as the technology and use progresses over the future.

Regulating these tools on a global scale is near impossible, even close to home (the U.S., the U.K., and Canada included) there are potentials for use without true science and fact, Lovell-Badge said. There’s no doubt this tool will be used and useful, he admitted, and beyond safety, “let’s figure out how to direct this to benefit all of mankind and not just the privileged.”

Image: Christopher Richardson, UC Berkeley, based on structure solved by Martin Jinek’s lab