The Academy's Herpetology collection of amphibians and reptiles is one of the 10 largest in the world, containing more than 309,000 cataloged specimens from 175 countries. Learn more about the department's staff, research, and expeditions.

David Blackburn

Academy Research Associate David Blackburn studies the evolution and distribution of frog species in Africa, along with the origin and spread of chytrid fungus, a major threat to frog species worldwide.

A Window into African History

It takes a finely tuned ear to describe the characteristics of a frog's call—is it chirping, trilling, or is that more of a chucking sound? Each frog's call is unique to its species, and by studying these animals, scientists like herpetologist David Blackburn are finding new evidence about how Africa itself has evolved. Highly sensitive to their surroundings, frogs can be very particular about the places where they live, and probably have been for 250 million years. When a frog's habitat changes, it often must shift to a more suitable area if it is to survive, so studying the modern-day distribution of frog species helps reveal the history of the landscapes in which they live.

In 2011, Blackburn was part of a small team which mounted an expedition to Burundi, a small but densely populated country which borders the vast Congo River Basin, the Great Rift Valley, and Lake Tanganyika—an intriguing geographic crossroads for biologists. Their objective: to seek out the long-lost Bururi long-fingered frog (Cardioglossa cyaneospila) which hadn't been seen there by scientists since 1949, during surveys conducted while the nation was under Belgian administration.

Since then, the country has seen political unrest, population growth, and habitat loss, so the research team was pleasantly surprised to find the habitats of the Bururi Forest Reserve were still relatively intact when they arrived. Blackburn had a hunch that the Bururi long-fingered frog's call would sound similar to that of its suspected relatives in Cameroon, more than 1,400 miles away. Sure enough, on the fifth night he found one on a log by following the sound of its call.

Scientists believe that many of the species in Burundi's high-elevation forests may be closely related to plants and animals found in Cameroon's mountains, suggesting that at some point in the past, a cooler climate may have allowed the forests to become contiguous between them. The lone long-fingered frog specimen collected, which now resides in the Academy's herpetology collection, can now be used for DNA studies to estimate how long the Cardioglossa species from Burundi and Cameroon have been genetically isolated from one another. The results will shed light on Africa's historical climate conditions, a topic that has far-reaching implications for understanding the evolution of life in the continent that gave rise to our own species. Events that impacted frog evolution, like a wet or arid period a million years ago, would also have affected human ancestors.

In the Field

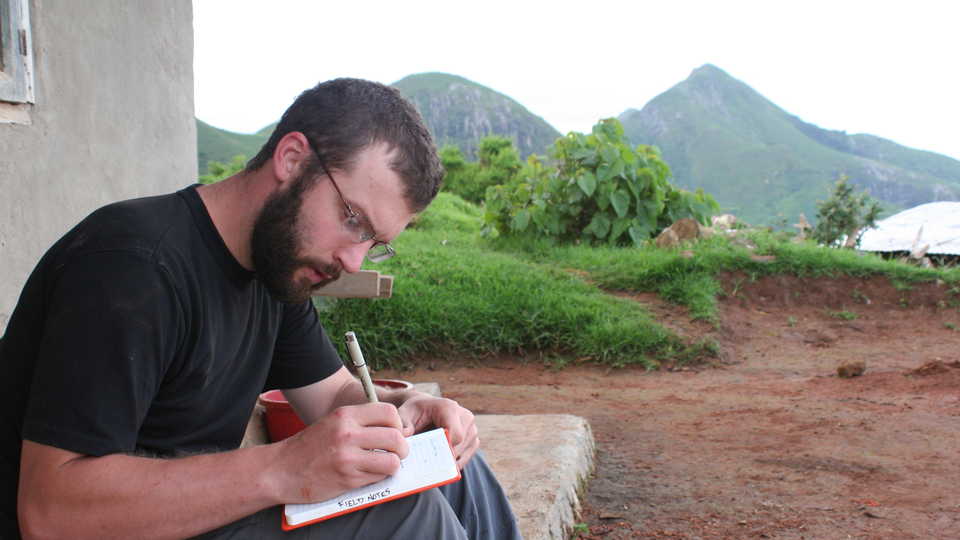

To answer big questions about the evolution and health of entire frog populations, Blackburn needs data, and lots of it. Museum collections are a valuable repository of what has been surveyed thus far, but to understand the current landscape and make comparisons, the only place to look is in the field, which for Blackburn usually means Africa.

On a recent expedition to eastern Nigeria, Blackburn and his colleagues enjoyed the relative comforts of a walk-in field station located a 45 minute walk from the nearest village. Large enough to house 10 people, the station features limited power from solar panels, hot water for showers (from a bucket on the stove), and intermittent satellite internet service. There is even a hill with a rock on it which gets some cell phone reception. It may sound rough, but these few conveniences at a central home base allow the team to be more efficient, which is a valuable commodity when you've traveled halfway around the world for a limited time. Very few field stations exist in Central Africa with interesting amphibian diversity, which is why Blackburn has cultivated a relationship with this one.

A typical day begins at 6:30 am with preparations for the day to come. Organization is crucial to keeping specimens and samples straight, and linking data points together back at home, so tubes and tags are all pre-labeled with corresponding numbers before stepping foot into the forest. After the team organizes its collecting and photography gear, and checks in on specimens collected the previous day, it's time for breakfast. Most days, Blackburn tries to squeeze in at least two collecting trips, hiking around ponds, streams, and forests for two to four hours at a time, usually in the late morning and then again beginning at sunset. By combining daytime and nighttime forays, the chances of finding frogs of interest go up, but it's a grueling schedule that can leave little time for rest.

Blackburn collects a variety of data points for each frog he finds, including its GPS coordinates, a description of its immediate habitat, photographs, a recording of its call (for males), and tissue samples. Blackburn also swabs each frog he encounters in the field to screen for a fungal pathogen responsible for many amphibian declines, and collects blood samples for parasite screening done in collaboration with the American Museum of Natural History. All of this information ends up online for scientists around the globe to access, and some frogs are preserved for reference collections at institutions like the Academy, which act as libraries of life.

Most expeditions also include appointments with permitting agencies, and educational meetings with local students and conservationists. Collaboration with local herpetologists before, during, and after every trip is crucial to success in the field, and is a two-way street. Several of Blackburn's African colleagues have visited the Academy and its collections to continue their own work.

A Deadly Fungus

Around the globe, amphibian populations are in rapid decline. Many modern frog species have been around for more than 3 million years, but today, one third of all known frog species are either extinct or endangered. Habitat loss and exploitation play a role, but it's the enigmatic declines—those which occur in seemingly pristine habitats—that really trouble Blackburn. And they're happening all over the world, across species lines and geographic boundaries.

In recent years, chytridiomycosis, a potentially deadly infection caused by the chytrid fungus (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis), has been identified as a major culprit. But how this fungus managed to spread across the world remains an area of active research among herpetologists (who study amphibians and reptiles) and mycologists (who study fungi). At this stage, they do not know where the fungus originated, but can see that something about its biology and/or distribution is changing.

Blackburn is also using museum collections at the Academy and other institutions to study the role African clawed frogs could have played. From 1941-1969, nearly 200,000 African clawed frogs were exported to research laboratories around the globe. Detailed records from a frog exporter in South Africa make it possible to pinpoint the time at which these frogs were introduced to specific addresses worldwide. Blackburn is screening research specimens from before and after that point to see when the fungus first appeared in native amphibians. Unlike most amphibians, African clawed frogs can carry chytrid fungus without being harmed by it, so invasive populations actually perpetuate the disease cycle among their native neighbors.

In Central and South America, historic specimens and field observations in the 1980s and onward provide evidence that the fungus spread from Mexico (in the 1970s) toward Panama (where it arrived more recently), wiping out a variety of local amphibian populations along the way. Knowing that a similar wave could one day sweep across Africa, Blackburn has begun swabbing every specimen he collects to screen for chytrid fungus, keeping his finger on the pulse of the situation.