Please note: Osher Rainforest will be closed for maintenance Jan. 14–16.

Science News

Bulked-Up T rex

October 17, 2011

Dinosaur fossils aren’t just for admiring in a museum. Researchers at the Field Museum recently put their famous Tyrannosaurus rex specimen, Sue, and four other related skeletons, through multiple tests to better understand how T. rex grew and moved. Their results reveal that these Cretaceous dinosaurs grew more quickly and reached significantly greater masses than previously estimated.

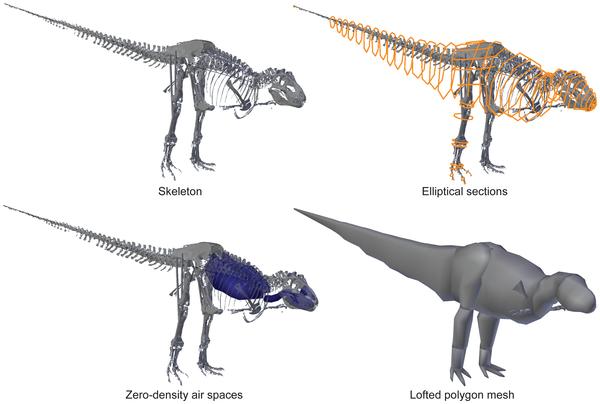

The team used 3-D laser scans of mounted skeletons as a template for generating fleshed-out digital models. Given their sizes (Sue is the largest, most intact T. rex fossil known), acquiring data for these specimens was a challenging task. Sue required four instruments that use light or X-ray technology and the collaboration of some unlikely partners—the forensics unit of the Chicago Police Department provided laser surface scans; Loyola University Medical Center generated scans of individual bones; and parts that were too large to fit in a medical scanner were sent to the Ford Motor Company in Michigan.

Then the researchers reconstructed digital body cross-sections along the length of each skeleton using the relationships of the soft tissues to skeletons in birds and crocodiles as a guide. A digital skin was then overlaid to generate a body volume, whose mass was calculated after empty spaces such as lungs and the mouth cavity were modeled and subtracted.

In order to appreciate the uncertainty involved in estimating how much flesh would wrap the skeleton of an extinct animal, individual body sections—the head, neck, torso, legs and tail—were modeled at three levels of “fleshiness”—from undernourished to obese.

Calculating the masses of the resulting virtual T. rex herd yielded some exciting surprises. The dinosaur appears to have been significantly heavier than previously believed. Sue weighed in at over nine tons. “We knew she was big but the 30 percent increase in her weight was unexpected,” says Peter Makovicky, curator of dinosaurs at the Field Museum. “Sue's vertebrae were compressed by 65 million years of fossilization, which forced a more barrel-chested reconstruction. Nine tons is the minimum estimate we arrived at using a very skinny body form, so even if we made the chest smaller, adding a more realistic amount of flesh would make up for the weight,” he explains.

The research also highlights the rapid growth rate of T. rex. Lead author John Hutchinson of the Royal Veterinary College explains, “We estimate they grew as fast as 3,950 pounds per year during the teenage period of growth, which is more than twice the previous estimate.”

Although a staggering number, it is in keeping with growth rate calculations for other dinosaurs. “Our new growth rate value actually erases a deficit between the previous growth rate estimate and what is expected for a dinosaur of this size,” adds Makovicky.

The rapid growth to gargantuan size came at the cost of speed and agility, according to the new study, which concluded that the locomotion of this giant biped slowed as the animal grew. This is because its torso became longer and heavier while its limbs grew relatively shorter and lighter, shifting its center of balance forward. Hutchinson describes it this way:

The total limb musculature of an adult T. rex probably was relatively larger than that of a living elephant, rhinoceros, or giraffe, partly because of its giant tail and hip muscles. Yet the muscles of the lower leg were not as proportionately large as those of living birds, and those muscles seem to limit the speed at which living animals can run. Our study supports the relative consensus among scientists that peak speeds around 10-25 miles per hour were possible for big tyrannosaurs.

The research was published last week in the open access journal PLoS ONE.