The Academy's Herpetology collection of amphibians and reptiles is one of the 10 largest in the world, containing more than 309,000 cataloged specimens from 175 countries. Learn more about the department's staff, research, and expeditions.

Science News

An Island-Hopping Mystery Solved

Academy researchers have uncovered the mysterious origins of the diminutive—yet prolific—Antillean whistling frog.

The Lesser Antilles archipelago harbors an abundance of species, some of which are found nowhere else on Earth. But because these islands have long been connected to one another by human activity, they pose a unique challenge for the biodiversity scientists who study them: Which species evolved on which islands?

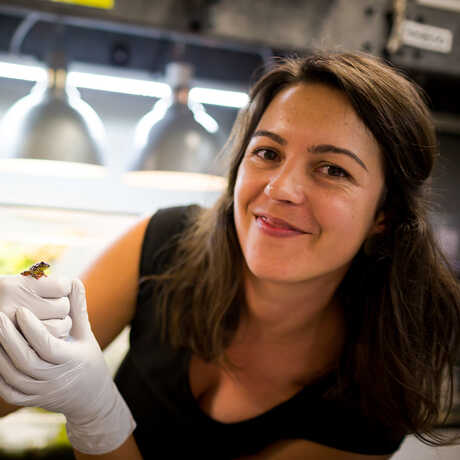

Though the Lesser Antillean whistling frog (Eleutherodactylus johnstonei)—bug-eyed and about the size of a thumbnail—can be found throughout the archipelago in staggering numbers, its native island is unknown. For Academy Curator of Herpetology Rayna Bell, PhD, solving the mystery of its origins—and those of other cryptogenic species, or species whose origins are unknown or uncertain—is critical for conserving island biodiversity. Bell and a team of collaborators conducted broad surveys across the Lesser Antilles, sampling frogs from populations on almost every island. “We were specifically looking for populations with more genetic diversity,” Bell says. Non-native species typically have lower genetic diversity, as all descendants would have come from just a handful of introduced individuals. After careful study of the frogs’ genetic makeup, the team was able to determine that E. johnstonei is native to the island of Montserrat, where the frogs had the highest genetic diversity, and that it has been introduced to every other island they’ve sampled so far.

Searching for native species

Since native species are often a conservation priority, cryptogenic species create somewhat of a headache for researchers and conservation managers alike. It becomes difficult to support both native and non-native species when their origins are unclear, especially in archipelagos where distinct island ecosystems are geographically close to one another. These difficulties are particularly pronounced in the Lesser Antilles, where species have been moved, intentionally and accidentally, between islands for millennia. “Identifying the native range of a species is key to conservation management,” says collaborating researcher Dr. Michael Lihan Yuan (Postdoctoral Fellow, University of California, Davis). “Without this knowledge, well-intentioned conservation efforts might be mistakenly directed towards species that are damaging native populations.”

For Bell, this research, conducted as part of the Academy’s Islands 2030 initiative, exemplifies both the challenge and importance of better understanding island ecosystems. “Invasive species on islands have much more of an impact than they do on continents,” Bell says. “If we want to protect species diversity, islands are among the best places to start."

Gifts of all sizes power Academy science around the world. Consider a donation to support island ecosystem research in St. Martin and beyond.

All photographs on this page: Gayle Laird © California Academy of Sciences