Science News

A New Fault on an Earthquake Anniversary

Twenty-seven years ago today, the San Andreas Fault shook with a 6.9 magnitude earthquake centered in the Santa Cruz mountains. The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake affected northern California from Monterey County to north of San Francisco, causing 63 deaths and $6 billion in damage.

So no wonder Californians became a little nervous a few weeks ago when a new fault was discovered parallel to the San Andreas Fault, near the Salton Sea, in addition to several hundred small quakes that occurred in the area and a warning for a potentially larger temblor.

The newly-mapped (and accidentally-discovered) Salton Trough Fault could impact current seismic hazard models in the earthquake-prone region that includes the greater Los Angeles area. These hazard models help protect lives and reduce property loss from earthquakes, says study lead author Valerie Sahakian. “To aid in accurately assessing seismic hazard and reducing risk in a tectonically active region,” she explains, “it is crucial to correctly identify and locate faults before earthquakes happen.”

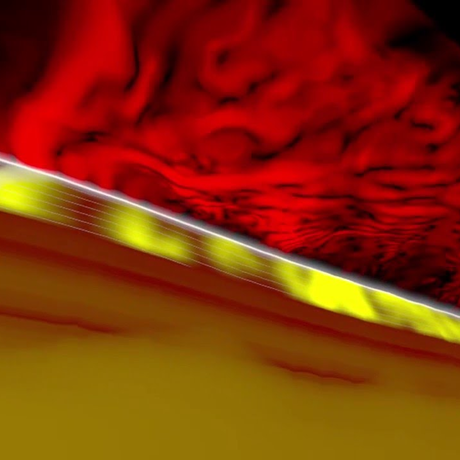

Researchers used a suite of instruments including multi-channel seismic data, ocean-bottom seismometers, and light detection and ranging (lidar) to map the deformation precisely within the various sediment layers in and around the Salton Sea’s bottom. The results reveal a strike-slip fault like the San Andreas Fault, meaning its motion is horizontal.

While further research is needed to determine how the Salton Trough Fault interacts with the San Andreas Fault, residents in the area are understandably shaken up. Other recent studies have revealed that the region has experienced significant earthquakes (magnitude seven or so) roughly every 175 to 200 years for the last thousand years. A major rupture on the southern portion of the San Andreas Fault has not occurred in the last 300 years.

“The extended nature of time since the most recent earthquake on the southern San Andreas has been puzzling to the earth sciences community,” says co-author Graham Kent. “Based on the deformation patterns, this new fault has accommodated some of the strain from the larger San Andreas system, so without having a record of past earthquakes from this new fault, it’s really difficult to determine whether this fault interacts with the southern San Andreas Fault at depth or in time.”

“We need further studies to better determine the location and character of this fault, as well as the hazard posed by this structure,” confirms Sahakian. “The patterns of deformation beneath the sea suggest that the newly identified fault has been long-lived and it is important to understand its relationship to the other fault systems in this geologically complicated region.”