P. punctata is native to the South West Pacific, from Australia to Japan, but it has a well-documented history of invasion. Today, there are known populations of white-spotted jellyfish in Hawaii, Puerto Rico, Gulf of Mexico, Brazil, and most recently, in the Mediterranean.

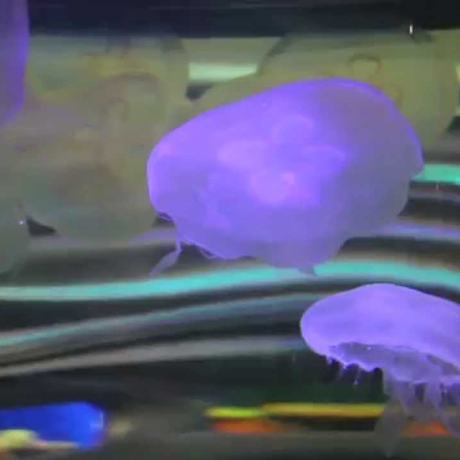

White-Spotted Jellyfish

This animal is not currently on exhibit at the aquarium.

Jellyfish are a favorite of Steinhart Aquarium visitors and it’s easy to see why: Their slow, mesmerizing movements and translucent bodies remind us how diverse—and strange—life can be. But as we gaze at these hypnotic creatures behind thick aquarium glass, their brethren are moving into ocean waters well beyond their natural range—and illustrating the impact a single species can have on an ecosystem when it’s introduced far from home.

Most species in Scyphoza, the class to which white-spotted jellyfish (Phyllorhiza punctata) belong, live their lives in two major stages: polyp and medusa. A medusa phase jelly, with its mushroom-shaped bell and long waving tentacles, is what we’re used to seeing. In contrast, the jelly’s polyp stage is sessile, fixed in place on the ocean floor. Ironically, this is the stage when jellyfish can travel farthest.

Human activity is likely responsible for the spread of P. punctata well beyond the species’ traditional range. Although polyps typically attach to rocks and other hard surfaces on the seafloor, they can also adhere the hulls of ships or offshore oil rigs. Additionally, before jellies become medusa, they enter a brief free-swimming stage and can be sucked up in the ballast water of large vessels. And because they feed on a wide range of organisms and tolerate low oxygen levels, juvenile jellies thrive in the polluted, nutrient-rich waters that are uninhabitable to many ocean dwelling animals. Overfishing has also accelerated their spread by reducing the numbers of jellyfish predators and competitors.

Range

Gulf of Mexico Invasion

In May 2000, a bloom of P. punctata broke away from the Loop Current, a flow of warm water that travels from the Caribbean northward to the Atlantic Seaboard, and settled in the Gulf of Mexico, where they decimated the region’s fishing industry. In massive numbers (around 10 million) the jellies clogged fishing nets and were so prolific and tightly packed observers claimed one could walk on top of the aggregation. Their numbers receded by fall, and while they’ve since returned to the area, nothing has rivaled the swarm of 2000.

Ecological Consequences

With each pulse of their bells, white-spotted jellies consume the larvae and eggs of fishes and crustaceans. This not only impacts an ecosystem’s reproductive capacity; it also reduces the food available to other species, as a single jelly can filter up to 13,200 gallons of water a day. Scientists are concerned that these ecosystems where P. punctata has been introduced are simply not equipped to withstand the species’ numbers and voracious appetite.

Be mesmerized by colorful coral reef fish, soaring stingrays, and adorable African penguins—streaming live to your device, 24/7.