Bob Drewes is living proof that you can turn your childhood passions into a lifelong career. Drewes was born and raised about a mile from Steinhart Aquarium in Golden Gate Park. Throughout his childhood, his home was filled with things he had found under rocks or picked up at the beach.

“I have always been deeply fascinated by weird stuff,” Drewes said.

He remembers one Academy exhibit that first fired his imagination as a child: “Strangely, it was the rotating tray of rocks that would appear normal under incandescent light and then glow brightly as they rotated under fluorescent light. As a toddler, I always gravitated to it.”

But upon reflection, what really changed his life was African Hall: “I fell in love with Africa in part because of the beauty of that hall and in part because of the influence of my great-uncle, Norman B. Livermore, under whose guidance it was built.” Livermore was the Academy's Chairman of the Board of Trustees during the Depression and war years.

“Like many of my schoolmates from my part of the city, I was raised to be either a doctor, lawyer, or businessman,” Drewes said.

It was a prospect that made him deeply unhappy. He did very poorly in his early undergraduate period, attempting to pursue a more traditional career path. Finally, he left school and served a tour of duty with the army Special Forces, an experience he found maturing.

When he finished his tour, Drewes married Gail, his childhood sweetheart, and returned to school.

“At this point, I was studying psychology, a field I found intuitive and really easy. At the same time, our little apartment on Potrero Hill was full of critters—some reptiles, two monkeys, and a coatimundi. One night as Gail fed our marmoset, she asked me, 'Bob, why on earth are you studying psychology?' From that moment on, I never looked back.”

Drewes completed his undergraduate degree at San Francisco State and his Ph.D. in Biology at UCLA, focusing on the evolutionary relationships of the dominant tree frog family of Africa, Madagascar, and the Seychelles Islands. His graduate career at UCLA also instilled in him an ongoing fascination with environmental physiology, the study of how individual organisms physically interact with the environment.

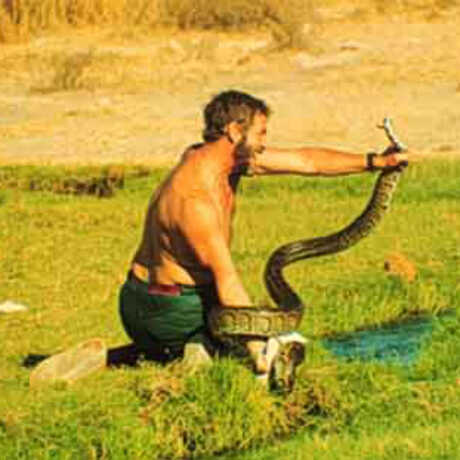

Bob's ongoing research on the systematics, natural history, and behavior of African reptiles and amphibians began with a year-long trip to East Africa in 1969, which he undertook with Gail and their then 9-month-old son, Bart.

“We got off the plane, and I was in Africa. Bob was home,” recalled Gail.

Drewes has returned to Africa every year since then. Drewes' long association with the Academy has created “a perfect base for someone like me,” he said. “I have the freedom to work in remote, poorly-known wild regions of Africa and at the same time to ask and answer fundamental scientific questions. And we have a collection of nearly 300,000 reptiles and amphibians from all over the world. If I'm doing an anatomical or morphological study, I can just grab specimens of related species off the shelf for comparison.”

“Imagine getting a job doing what you love more than anything else within the most venerable scientific institution in your own city," Drewes said. "How can I describe that? I've had 38 years of adventures in the African bush observing and catching weird critters. And I've also experienced the unbelievable thrill of academic discovery. It's been a hell of a ride.”