Sorry, I love titles like this… and I have more! Actually, there are no toads (Bufonidae) on São Tomé and Príncipe; interesting in itself because seven other amphibian species of five different families have survived the ocean crossing during the many millions of years since the islands first emerged. Moreover, toads are common in almost every conceivable terrestrial mainland habitat.

My last two blogs have been a bit academic. Having laid the biogeographical ground work, it is probably time to get back to the unique, endemic island critters. The tiny, 31-million year old island of Príncipe is the only home of Africa’s largest treefrog, Leptopelis palmatus – the Príncipe Giant Treefrog. It is one of the world's rarest frogs, as well.

L. palmatus – D. Lin phot. GG I

Let me be quick to point out that the Príncipe critter is not Africa’s largest frog; that title belongs to Conraua goliath (below), which is found on the mainland in southern Cameroon and Gabon. In fact, the goliath frog is the largest in the world but it is not related to any on São Tomé and Príncipe-- no members of its family have made it across the saltwater gap to the islands, or if they ever did, they have not survived.

Conraua goliath—J.-L. Perret phot.

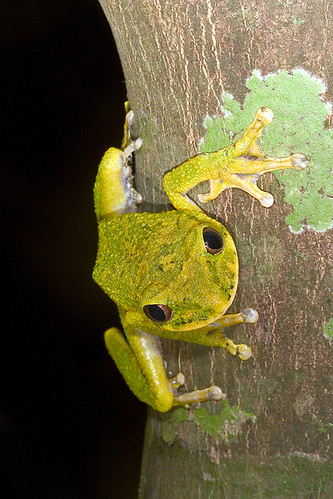

Leptopelis palmatus is the largest African treefrog (emphasis on “tree”) -- frogs that are adapted for climbing with, among other features, enlarged finger and toepads. As I have pointed out in earlier blogs, gigantism is a relative thing; the giant endemic plants, frogs, birds and lizards of São Tomé and Príncipe are bigger than all of their relatives but they are not necessarily so large you trip over them (like Galapagos or Aldabra tortoises); they are simply larger than all of their relatives. The two images below put this frog in some perspective, and I think you will agree that this is one BIG treefrog.

Me, with the first female. R. Stoelting phot. GG I

The frog on Dong Lin, our photographer. R. Stoelting phot GG I

This species was first described in 1868 on the basis of a single female specimen, housed in the Berlin Museum. At the time of GG I in 2001, the Príncipe giant treefrog was known only from this single type specimen and seven additional specimens, all females, collected by local Príncipeans for a Swiss colleague named Catherine Loumont. The largest of Loumont’s specimens is 110 mm from snout to vent (we do not include legs when we measure frog sizes), and even after our years of work, this specimen remains the largest ever found – it is nearly 30 mm longer than its nearest mainland relative, Leptopelis macrotis, distributed from central Sierra Leone to Ghana. One of several differences between the two species is the striking deep-red eyes of our island endemic.

The eye of the Príncipe giant treefrog. D. Lin phot. GG II

This first specimen we found during GG I (first three treefrog images, above) was yet another female, 108 mm in length. Our mammalogist, Doug Long, was led to the critter by some kids from the now-defunct plantation of Sundi in northwest Príncipe. Sundi may no longer function as a plantation but it is still inhabited by the descendents of former workers—lots of them, there is even a mayor.

Doug Long and the Sundi kids. RCD phot. GG I

The arrival of this frog was greeted with great enthusiasm by yours truly; here in my hands one of the rarest frogs in the world! And it was huge! I was not surprised to learn that it had been found on the ground, as it is hard to imagine something so bulky climbing around in bushes and trees. The male of this species was completely unknown, so far as we knew at the time,. None had ever been collected, photographed nor described in the scientific literature. So we also knew nothing about the species’ breeding biology, male advertisement call or tadpole. At the time, we were unaware of a blog posted two years before our visit by Jonathan Bailey on the Gulf of Guinea Conservation Group website, entitled “One month in the Forest of Príncipe.” Jonathan (now Dr.) Baillie described hearing the calls of male L. palmatus as “like a pop bottle being continuously opened." He heard them high up on Pico do Príncipe near a small stream at about 700 m and actually collected two of them which had been deposited in the Natural History Museum in London. But during GG I, the male giant treefrog was terra incognita, so far as we were concerned.

Second female from Rio Papagaio. J. Ledford phot.. GG I

During a second GG I visit to Príncipe a few weeks later, my then-graduate student, Ricka Stoelting, collected another female along the Rio Papagaio, a large-ish river that flows through Príncipe’s only town, Santo Antonio. It was also of a rather dull in color but with white spots. We have since learned that this is about as brightly colored as females get.

Rio Papagaio in town, downstream. RCD phot. GG III

Ricka Stoelting, my graduate student on Sao Tome. RCD phot. GG I.

During this second visit, Ricka and Dr. Sarah Spaulding ascended Pico do Príncipe to the top and camped at nearly the same spot where Jonathan Baillie had been two years before. There she found the males, lots of them, calling from bushes and branches at night near a very small creek.

Tiny creek on the Pico. J. Uyeda phot. GG II

Ricka brought the series of males back down the mountain, and they were astounding. Unlike the females they were very brightly colored and highly variable, in pattern, as well; this variability is rather unusual in frogs, although there are some species that are sexually dimorphic for color. And they were much, much smaller than the females, though we knew they were full-sized breeding adults. During later analysis we learned that the largest breeding males are only about 41% of the size of the largest females, a size disparity that is striking.

First series of live males (far right is a juvenile). J. Ledford phot. GG I

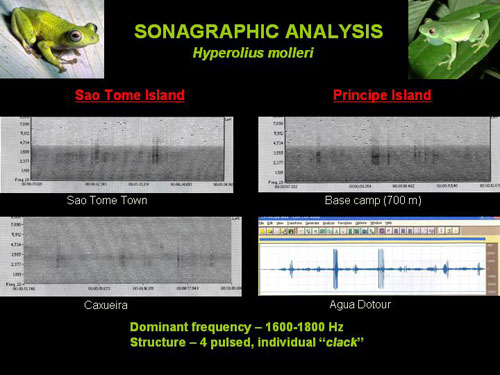

Ricka never heard them calling and anyway she had no way of recording them if they had. One of the parameters we use in establishing relationships among frog species is analysis of the voice (or advertisement call.). Males call to attract females, and at the same time to advertise their presence and territory to other males. The advertisement call is species- specific and obviously adaptive when there are other species utilizing the same water for breeding. To really define Leptopelis palmatus, I needed a recording of the voice, and this was to become a priority in the future. Below is a preliminary analysis of the call of another Gulf of Guinea frog species which we think is present on both islands. Here, we are comparing the advertisement calls of males from two different localities on both islands, and we can see that they are basically the same.

Preliminary sonograms of Oceanic treefrog. Marshall/Drewes construct.

Back at the Academy, Ricka and I prepared the first formal description of male Príncipe giant treefrogs. Now aware of Baillie’s blog, we read his word description of the advertisement call. Although the Principeans insisted the frogs did call, it remained an open question, especially when I learned from anatomical study that the male frogs lack vocal sacs and vocal sac openings, features that most calling frogs possess (including other members of the genus Leptopelis). GG II in 2006 included Josef Uyeda as my student (now a PhD candidate at Oregon State University). Josef was working on a different group of island endemics called puddlefrogs (see earlier blog: “We Find Jita”) but when we were on Príncipe, I sent him up the Pico with his friend Mac and the same guide, Manona, who had led Jonathan Baillie and Ricka years before. They were armed with my old Sony cassette recorder (my iPod had failed). Bear in mind that the only known localities for males were at nearly 700 m, high on the Pico and while this made no biological sense, that’s where my stalwarts had to go. This is no small matter given the topography of the island, but graduate students are good at this sort of thing and anyway, they tend to be younger and more vigorous than their advisors!

Principe terrain. Pico do Príncipe is in the clouds to the left of the large Pico Papagaio. R. Wenk phot. GG III

Josef Uyeda hunting for caecilians on São Tomé. D. Lin phot. GG II

While in the same general area as earlier workers at about 700 m, Josef got a lot done but the party was caught in heavy rains. He heard males and saw them calling but only managed some rather distant, poor-quality recordings (the conditions were miserable), but now at least we knew that the frogs did, indeed, call. GG III, last spring, provided some answers, thanks in part to our friend Ramos of Bom Bom Island. Ramos is assistant manager of the resort, a native Principean and a keen, observant naturalist. See the photo of Ramos in the “We Find Jita” blog. I described our past difficulties in trying to record the voice of the Príncipe giant treefrog to him, and he grinned and said, We will go to my roça (farm) on Pico Papagaio and at 5:30, we will get them! I was highly skeptical…

Roça Papagaio, Ramos’s farm at 250 m. R. Wenk phot. GG III

Ramos’s farm is in the forested area on the northern flanks of Pico Papagaio at about 250 m. Just before you reach it on a dirt steep uphill road, you cross a tiny creek; this is where Ramos took us – about 30 m up that small creek, thick with dense undergrowth, and there we sat, waiting for the forest cacophony of grey parrots, mona monkeys to subside. Nothing much happened. I had my iPod with recording head at the ready. We waited in the gathering gloom for about 20, maybe 30 minutes, Ramos grinning throughout and occasionally exclaiming, Just wait. We will get them!

Me waiting, iPod in hand, for the giants to call. T. Daniel phot GG III

And sure enough, we began to hear frogs calling. I looked at my watch. It was 5:30.The call is certainly a strange one; it lacks resonance (remember males don't have a vocal sac) and thus it is rather flat and unmelodius. Rather than my trying to describe it or arguing with earliler descriptions, you can listen to it yourself:

[display_podcast]

And here are a couple of photos of the male that was calling, taken by Wes. These are un-posed and before we collected it as a voucher specimen for the voice:

Weckerphoto GG III

Weckerphoto - GG III

There are still great gaps in our knowledge of this most unique frog. Obviously, the males are well-distributed in the lower elevations; we just have not been in right place at the right time. We still cannot explain why females are dull and rather cryptic in coloration and usually found on the ground, while there appears to be no selection for color in males. The dull color of females seems consistent, as a couple of months ago I found six additional females (no males) collected in 1988 at the Doñana Institute in Seville and they were clearly drab in life; my colleagues at Donana tell me they were collected on the ground in lowland localities at Rio Papagaio and Bela Vista.

Six female Seville specimens at Donana Institute. RCD phot.

We still have not observed breeding, nor have we ever seen tadpoles. In this genus, Leptopelis, they are very distinctive, and I would predict the tadpole will look like this:

A Leptopelis tadpole. Image courtesy of Dr. R. Altig

Here’s the parting shot:

Nezo, of Angolares, Sao Tome: artist, musician, restaurateur and worthy man - Weckerphoto GG III

PARTNERS We gratefully acknowledge the support of the G. Lindsay Field Research Fund, Academy Research Venture Fund of the California Academy of Sciences, the Société de Conservation et Développement (SCD) for logistics, ground transportation and lodging, STePUP of Sao Tome http://www.stepup.st/, Arlindo de Ceita Carvalho, Director General, and Victor Bomfim, Salvador Sousa Pontes and Danilo Bardero of the Ministry of Environment, Republic of Sao Tome and Principe for permission to export specimens for study, and the continued support of Bastien Loloumb of Monte Pico and Faustino Oliviera, Director of the botanical garden at Bom Sucesso. Special thanks for the generosity of four private individuals, George F. Breed, Gerry F. Ohrstrom, Timothy M. Muller and Mrs. W. H. V. Brooke for making these expeditions possible.