What Makes a New Species a New Species?

When high schoolers Prakrit Jain and Harper Forbes came across a yellow, semi-translucent, unidentified scorpion photographed by a user on the iNaturalist app, they had a hunch that it might be a new species. For two years, the teenagers went back to the San Joaquin Desert in Tulare County where the scorpion was first located, in search of the elusive arachnid.

This year Jain and Forbes, under the supervision of the Academy’s Curator of Arachnology Lauren Esposito, PhD, eventually found the scorpion in 12 locations across the Central Valley and identified it as Paruroctonus tulare (P. tulare). Genetic testing and comparisons of their claw sizes found that P. tulare was, in fact, a brand new species—and that there was overwhelming evidence that local development, agriculture, and flooding had rendered it endangered.

As climate change and habitat loss threaten animal, plant, and human populations across the world, it’s essential to understand what we risk losing. By conducting ongoing biodiversity research, we can identify species new to science and develop specific conservation solutions to protect them.

You might be wondering why the Academy calls new species “descriptions” rather than “discoveries.” Some communities hold deep knowledge about local ecosystems that are not well-documented in Western science. This newly described succulent, Pachyphytum odam, has long been known to Mexico's O'dam community as da’npakal, meaning bald or slippery.

Arturo Castro-Castro © California Academy of Sciences

In the last decade, Academy scientists and research affiliates have described nearly 2,000 new species, ranging from tiny sea slugs to flowering plants and never-before-seen deep-sea coral reef fishes. This year, 26 researchers across five fields described 153 new species, including 19 new species of flattie spiders from Australia and 20 new nudibranchs, or sea slugs.

2023 also marks the fiftieth anniversary of the Endangered Species Act (ESA), a federal framework for protecting threatened and endangered plants, animals, and their habitats. As Academy researchers search for rarely seen animals and plants during field work, they are also looking for species that might need more protection. A handful of the 153 newly described species are now under consideration for the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Endangered Species List.

“Naming and describing species is the first critical step in knowing about them and protecting them in a meaningful way—it is the tip of the iceberg that sets us on a journey to understand their role in healthy ecosystems,” said the Academy’s Dean of Science and Research Collections Shannon Bennett, PhD. “Formally cataloging biodiversity also sets in motion codified processes for protection, from the species level (through the ESA) to the ecosystem levels (through designating sanctuaries or Marine Protected areas).”

Finding a new species can be pretty simple—if you know where to look and what to look for.

Over more than two decades researching spiders, Academy researcher Sarah Crews, PhD, has developed a systematic approach to finding flattie spiders (of the Karaops genus). When Crews turned her focus to the Australian arachnids in 2010, scientists had only identified one Karaops spider species from the entire continent. Today, Crews has described more than 50 flattie spiders, including 19 in this past year alone.

“Flattie spiders are extremely fast and really flat—scientists and researchers just don’t bother with them because they’re not that easy to catch,” Crews said. “You can find flattie spiders lurking under pretty much every rock pile in Australia, if you’re targeting them specifically and know to look for them at nighttime."

Flattie spiders have the fastest turning strike of any terrestrial animal. They can turn at a maximum speed of 2,800 degrees per second, which is faster than a DVD player. Sarah Crews, pictured, says flattie spiders tend to live under rocks and bark in Australia, venturing out at night to feed.

Sarah Crews © 2023 California Academy of Sciences

The years researchers spend “in the field”—in the jungles of the Galápagos, on hikes through California’s Sierras, or in deep-water dives in the Indo-Pacific—helps them develop a near-encyclopedic knowledge of the animals and plants in a given area. The Academy’s Senior Curator of Invertebrate Zoology and Geology Terry Gosliner, PhD, is a taxonomic expert in nudibranchs who has found at least one new species every year since 2011. In 2023, Gosliner helped describe 20 new sea slug species hailing from the Atlantic and coral reef systems along the Indo-Pacific’s mesophotic (100-500 feet below the surface) regions.

How’s he so good at locating these teeny-tiny, millimeters-long sea slugs? Time, teamwork, and a ridiculously good memory.

“I was recently diving in Fiji, where I saw a tiny soft coral that looked like a button,” Gosliner said. “I remembered finding another sample like it in Guam, some 30 years ago—turns out, it was a new species and only the second time someone had seen this coral.”

When sifting through sand for new sea slugs, Gosliner says he keeps an eye out for strange spots, spikes, and unique patterns that might hint at a new or rarely seen species; but other factors like distribution and range can help researchers understand a given animal’s uniqueness and importance to a region’s ecosystem.

“There’s a lot of undocumented diversity out there, and insects and invertebrates are some of the most poorly studied animals there are,” Gosliner said. A historic lack of research into insects and invertebrates might just be behind the disproportionately large numbers of new species described in these fields: Since 2010, roughly 70% of the Academy's new species descriptions stem from entomology and invertebrate zoology.

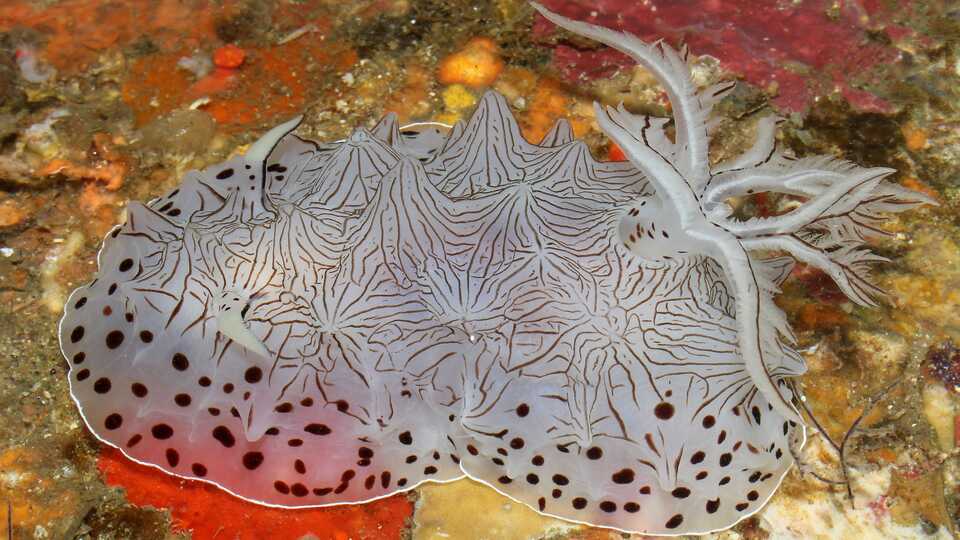

Terry Gosliner and three other researchers described four new Halgerda species from the Indo-Pacific’s mesophotic zone, including Halgerda scripta (pictured). The sea slug's ancestors were predominantly located in shallow waters, but one branch of the family tree migrated into the ocean’s deeper waters, leading to these new species discoveries.

Terry Gosliner © California Academy of Sciences

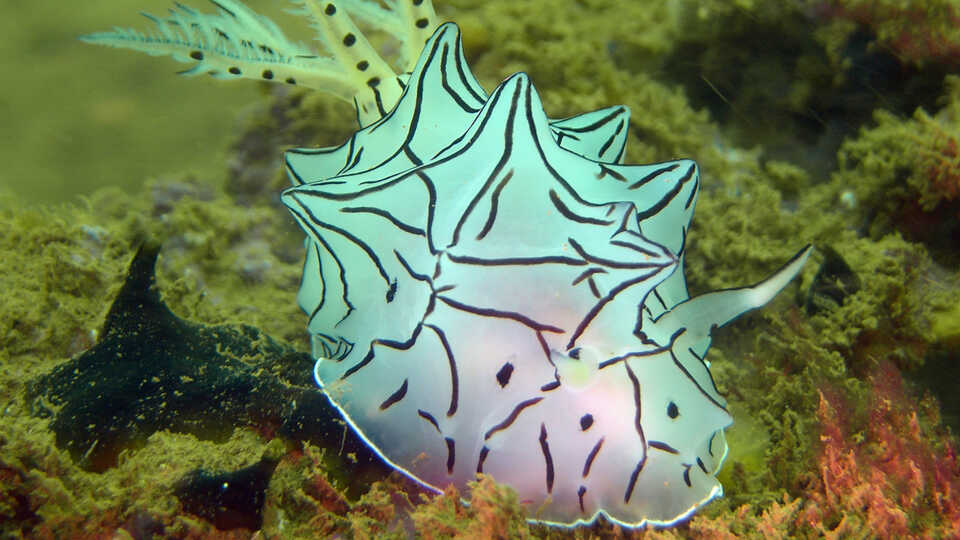

Halgerda hervei's white-and-black coloring is due to a lack of light penetration at mesophotic depths. Jean Francois Herve © California Academy of Sciences

This nudibranch, Halgerda berberiani, features yellow coloring typical of Halgerda nudibranchs from shallower areas of the ocean. Anthony Berberian © California Academy of Sciences

Though many species descriptions start with field observations, much of the work that goes into describing a new species happens on collected specimens.

“We go out there to gather specimens and add to our collections, whether they’re common animals or new species,” Gosliner said. “The purpose is to build a material library—a biodiversity baseline—to help us study an animal’s genetics and really understand their evolutionary relationships to each other.”

Researchers use collected specimens as a way to study certain morphological traits—outward characteristics and the structure of body parts, like bones or scales—that may differentiate an animal from near relatives. Crews, for example, notes that most scientists will look at the genitalia of insects, spiders, and other arthropods in order to tell different species apart.

The distinctive cow-like spots gave away this Lady Elliot goby, newly described by Mark Erdmann, PhD, a research associate at the Academy. Erdmann stumbled upon the tiny goby in the sand while mapping the biodiversity around Lady Elliot Island, located at the southern end of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef.

Mark Erdmann © 2023 California Academy of Sciences

Erdmann, a research associate at the Academy, said that his team was able to identify a new shrimp goby species (Tomiyamichthys elliotensis) after a lengthy group effort: Erdmann dove along the southern waters of the Great Barrier Reef to collect the tiny, spotted fish, while researchers Gerald Allen, PhD, and Christine Dudgeon, PhD, took those samples to the lab to count the animal’s scales, document its coloration, and study the shape of its teeth.

“Describing a new species is truly a collaborative process, and we often involve a geneticist to test fin ray clips—that’s enough to do DNA barcoding, which helps us place animals on the tree of life,” Erdmann said. “It’s not always accurate, but it helps confirm the differences and unique traits that we can observe with our eyes, such as color or iridescence.”

DNA testing and genetics have become increasingly important tools in confirming new species descriptions. Nicknamed “barcoding,” scientists use this analogy to describe the process of analyzing tiny snippets of a specimen’s genes, much like a product barcode allows a retailer to distinguish one item for sale from the next.

All 153 new species described by Academy researchers will be added to the tree of life, a phylogenetic tool similar to a family tree that scientists use to describe the evolutionary history and relationships among species.

Yet researchers say that these new species descriptions are essentially hypotheses; many of them may be disproven or altered in the future once novel scientific approaches become available. This year, for example, Academy botanists revealed that a common flowering plant from Costa Rica was mistakenly categorized as a separate, similar species for more than 150 years.

There is no code in zoology that requires specific tests, DNA analyses, or morphological comparisons to determine what a “new species” really is. But because a species is a hypothesis, researchers like Esposito want each new description to hold up to scientific rigor and scrutiny by other scientists.

Lauren Esposito says there are more than 35 different theories for defining a species. Her favorite? The phylogenetic species concept: It says that a species is something that is diagnosable, meaning you can look at an animal and recognize that it’s different from its closest relatives.

Kathryn Whitney © 2016 California Academy of Sciences

At the Academy, researchers have used new species descriptions to fight for the protection of rare animals that are endemic to specific islands or oceans. The new arachnid described by Jain and Forbes marks the first-ever scorpion description where the IUCN’s evaluation for potential endangerment listing has been conducted at the same time as the new species’ publication. And Gosliner’s discovery of four new mesophotic sea slug species means that ocean conservation efforts should benefit both mesophotic and shallow water regions.

"We must document the Earth's living diversity so that we can work to protect it, and the California Academy of Sciences is honored to take part in this critical global effort," said Academy Executive Director Scott Sampson, PhD. "Additionally, we must aim beyond protection toward regeneration, boosting the health and resilience of ecosystems for future generations of humans and nonhumans alike. Here, too, the Academy is deeply engaged through our bold mission to regenerate the natural world.”

Prakrit Jain uses the iNaturalist app to take a photo of a scorpion he found at the Windy Hill Preserve. Gayle Laird © 2022 California Academy of Sciences

Human-driven pressures like climate change and agricultural development motivated Jain and Forbes to seek out ESA protections for the new scorpion. Prakrit Jain 2023 © California Academy of Sciences

- You can discover species, too! Download the iNaturalist app and join a statewide effort to look for and document all species of sea stars along the coast between now and Dec. 27.

- Contact your lawmakers about the ESA: Consider signing this petition by the Aquarium Conservation Partnership, asking President Joe Biden to create a comprehensive biodiversity strategy to strengthen conservation and regeneration efforts nationwide.

- Visit and support the California Academy of Sciences: New species research is made possible by the Academy’s generous visitors, donors, and affiliates. Plan your visit today.